Dear Friends,

This is the second preview of what the paid-tier essays of It All Connects will be like. It develops further an experience I had when I was in my late twenties that I wrote about in Four By Four #39: going to visit a man who was dying of AIDS with my grandmother and her friend Herbert, a man whom I intensely disliked at the time but who nonetheless gave me gifts that I still have after all these years. Writing this piece gave me a chance to reflect on what those gifts have meant to me, even if I did not realize it until very late, and on what I might have missed by not acknowledging them for what they were when I received them. That kind of self-discovery is one of the things I value most about writing, and I am grateful that you’ve allowed me to share that process with you.

Please note that some images in this post are NSFW.

—Richard

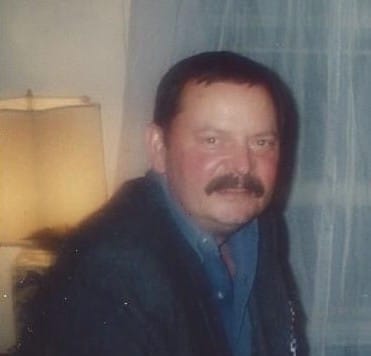

I was scrolling through my photos the other day when this picture of my grandmother’s friend Herbert caught my eye. Herbert was European, though I either don’t remember or never learned what country he was from, and he had a European elitist’s stereotypical disdain for American culture, from food to clothes to literature to music. He never openly insulted me, but he made no secret of the fact that he thought someone of my “obvious intelligence” ought to have “aimed higher” in my tastes and interests. If I didn’t call him out as the snob he was when my grandmother managed to nudge us into the kind of intellectual debate she liked to watch, it was, first, because I didn’t want to disrespect someone who seemed old enough to be my parent—though I never learned exactly how old Herbert was—and, second, because my grandmother so obviously adored him.

Herbert was, however, a very good storyteller. He was well-traveled and had a writerly flair for conjuring the places he’d been to with just a few details. He’d served in either World War II or the Korean War—I don’t remember which—and he told some marvelous tales of the time he spent in Japan, though all I remember of them is that they were marvelous. He started sharing those stories with me after I came back in 1989 from the year I spent teaching English in South Korea. It never occurred to me that he might have been doing so because he saw them as a way for us to connect in ways we hadn’t been able to do before, and I wish now that I had not been so quick to dismiss them, since they are connected to some gifts that he gave me, or, to be more precise, that he gave my grandmother to give to me on his behalf.

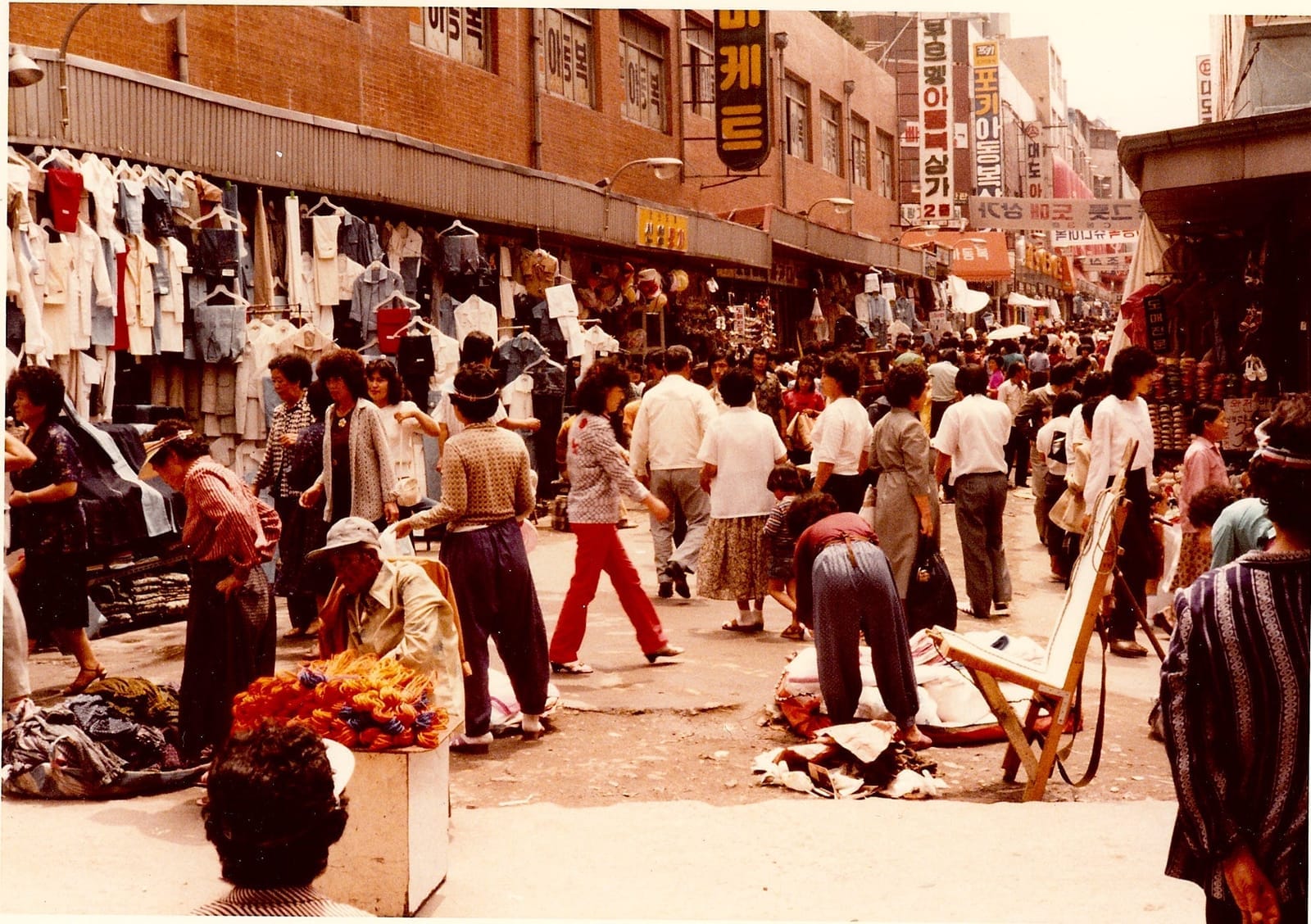

First is a series of photographs someone took—maybe him, maybe not, I never knew—when they were in Korea ten or twenty years before I was. Some of them are obviously of places in Seoul, but none are labeled with a specific location. Nonetheless, they evoke for me even now the places in Korea where I lived, worked, and played. These two, for example, remind me viscerally of what the Saemaeul Shijang, an outdoor market across the street from my apartment, was like when I was there.

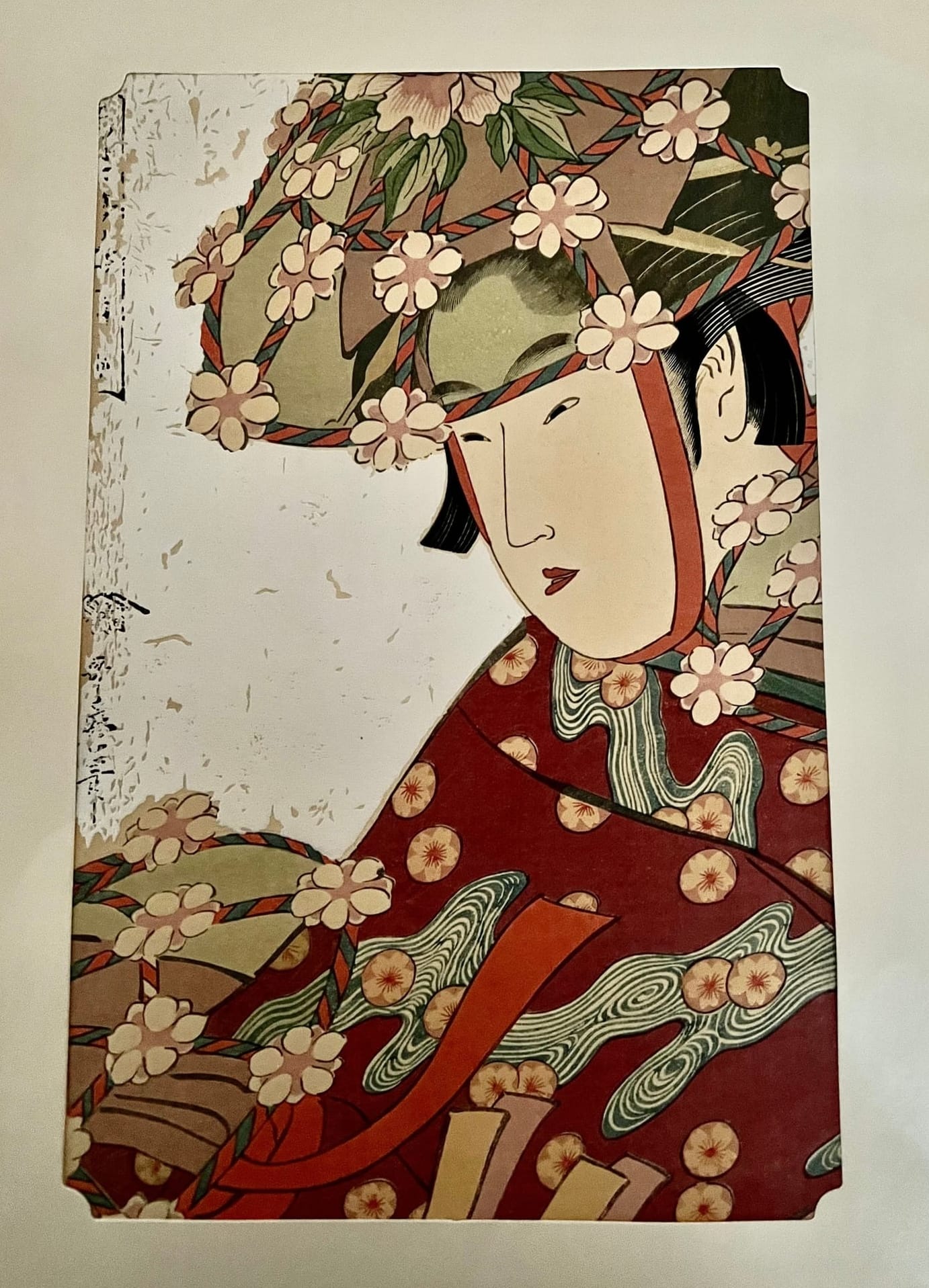

The second gift I received from Herbert was a set of three Japanese prints. This one is a reproduction of a print by Kitagawa Utamaro, “The most celebrated artist of women of the whole ‘Ukiyo-e’ school,” according to the British Museum’s website.

The title of the image is Yogoto ni Au Koi (“Love That Meets Each Night”), suggesting that the letter the woman is pulling from the breast pocket of her kimono is from a lover who wants to meet her. It’s from a series called Kasen Koi no Bu (“Anthology of Poems: The Love Section”), which Wikipedia describes as

a series of five ukiyo-e prints…published c. 1793–94 [the titles of which] parod[y] the section headings in waka and kyōka poetry anthologies…The women depicted are not courtesans or others employed in the pleasure districts, who were the typically subjects of ukiyo-e portraits of beauties.

The other two prints Herbert gave me are also reproductions. The one on the left is of a 1925 woodblock print called “Yuku Haru” (“Departing Spring”) by Kawase Hasui, which depicts a young woman who is most likely a maiko, an apprentice geisha. The one on the right, also by Utamaro—at least according to Google’s AI, since I could find no identifying information on the reproduction itself—is from a 1790s series called Tôsei Odoriki Zoroe (“An Array of Dancing Girls of The Present Day”). It depicts a young woman in a festival costume that represents the Heron Maiden, a character from a kabuki drama that was popular at the time.

While researching these images, I also discovered that Utamaro was known for his erotic art. This one, among others, can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website:

When my grandmother was moving out of the apartment she’d lived in for more than fifty years, long after Herbert died, she gave me something else he’d given her to give me, though she’d either forgotten to do so or had decided it would be inappropriate.

I was disappointed both that I would never learn the story of where and when Herbert bought these plates and that I could not ask him how he felt about them. My grandmother had told me years earlier that Herbert was a devout Roman Catholic—he’d either converted or rediscovered his faith; I don’t remember which—and, in keeping with that tradition, he’d chosen to live according to the principle that being gay was not a sin, but that gay sex was. Even by the time I met him, she said, he’d been celibate for decades. I would have loved to hear Herbert talk about what the eroticism of those images meant to him, especially since the Church’s teaching that celibacy was the only way for him to be gay and not at the same time sexually sinful felt to me oddly parallel to the celibacy that the Church demands of priests.

§§§

The gift that Herbert gave me that motivated me to write this post was actually bequeathed to me by someone else.

This Le Creuset enameled cast iron oval baking dish—the color is called “Flame”—originally belonged to a man named Michael, whom I met only once, when I accompanied Herbert and my grandmother on a visit not too long after I returned from Korea. Michael was dying of AIDS. His family had disowned him, and Herbert was one of the people helping to make sure both that he was not alone and that he was as comfortable as possible as death approached. I remember a pale, gaunt man with short-cropped red hair and a neatly trimmed beard and mustache propped up on pillows so he could watch TV. His face lit up when we entered the room. It was the first time I’d ever been in the presence of someone who knew he was dying, and I did not know what to say. I was grateful, therefore, that Herbert did most of the talking, though I have no memory at all of what we talked about.

Some months later, my grandmother and she told me that Michael was gone. We were sitting at her dining room table, waiting for Herbert, who was coming to have lunch with us. She’d been helping Herbert go through Michael’s belongings, she said, trying to figure out what to do with the things Michael had not designated for specific people, and they’d been having a hell of a time trying to figure out how to dispose of the sexual paraphernalia they’d found—dildos, cuffs, ball gags, and so on—without embarrassing either themselves or, posthumously, Michael. I laughed out loud as my grandmother listed those items as if they were as ordinary as forks, knives, and spoons.

When Herbert arrived, he was carrying the baking dish. “Michael remembered you vividly from our visit,” he said. “When I saw him next, he said about you, ‘That is a good, kind, decent man.’ I told him you liked to cook and so, as we were making his final arrangements, he said he wanted you to have this.” It’s hard for me to imagine now what Michael saw in me during the short time we were together, since I don’t remember saying more than a few words. I thanked Herbert, but I don’t think I said anything else, not knowing how, given my feelings about him, to acknowledge what I understood to be his implicit agreement with Michael’s opinion.

Not too long ago, as I put into the oven the fresh-caught cod covered in a tomato-cilantro-cumin sauce that we were going to have for dinner, it occurred to me that I think about Herbert and Michael every time I use that baking dish. That started me thinking about the ways in which Herbert had woven himself into the fabric of my life through the things he gave me, and I realized that I’ve been carrying for decades a gratitude for those gifts that I wish I’d understood well enough to express when I received them. Herbert is gone now and will never know. I am glad, though, that I’ve finally expressed it.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion