A Cautionary Tale

Two Khorasani darvishes were traveling together. One of them, because he fasted for two days at a time, was weak. The other ate three meals a day and was correspondingly strong. They came to a town where they were arrested at the gates on suspicion of spying. Their captors threw them into separate cells, the doors of which were then walled up with mud bricks. The dervishes’ innocence was not proven until two weeks later, but when the doors were opened, the stronger man was discovered to have died, while the weak man had survived.

The townspeople were surprised, but a wise man among them pointed out that the opposite circumstance would have been even more surprising. The one who’d eaten three meals a day died because he lacked the wherewithal to withstand the hunger his captivity forced upon him. The weaker dervish survived because his habit of fasting prepared him for that hunger.

A man whose appetite is very small

will not be overwhelmed by any hardship,

but a man who thinks that eating signifies

his wealth—if hardship overtakes him, he’ll die.

—from Golestan by Saadi of Shiraz, translated by Edward Rehatsek and Richard Jeffrey Newman

Four Things To Read

Let Our Bodies Change The Subject, by Jared Harél:

Overnight

A daughter returns to you

with three new freckles

and the purple stain

of popsicle on her tongue.

She gives nothing but what you glean

from slimmed features,

sneakers gone old, the black hole

of a backpack she shrugs

off her shoulders

to race unencumbered

towards her friends

down the street.

Just yesterday she clung

to the nape of your t-shirt,

begging to stay.

Just yesterday

she was yours, and you,

you gave her away.

Let Our Bodies Change The Subject is a lovely, moving, and sometimes unnerving meditation on what it means, in a world where you are surrounded by so many different kinds of threats, to live in and with family, in particular what it means to bring children into that world and to love them, fully and unconditionally, knowing that they will ultimately make their way through it on their own terms and well beyond the reach of your protection. Harél is a marvelous observer of the small details of family life, both the one in which he grew up and the one he has made with his wife; but what lifts those small moments out of the mundane, what turns his observations into moments that you, the reader, want to live within is his craft. His speaker sounds plainspoken, but look closely at the way Harél constructs his lines and you’ll see the work of someone who cares deeply about craft. Take a look, for example, at the first three lines of “Beer Run:”

It was summer. I was small. My uncle plunked me

into his pickup to keep him company

on his run for more beer. I was glad to go.

I’m not going to do it here, but map out the sound patterning within and across those lines and you’ll see just how meticulously crafted the speaker’s conversational voice really is. Speaking as a poet, that commitment to craft as the thing that makes a poem a poem—something which is all too often missing in a lot of the poetry I read these days—is a large part of what made this book so enjoyable.

§§§

“The Schools That Are No Longer Teaching Kids to Read Books,” by Xochtil Gonzalez:

Knowing how to read is crucial, but loving to read is a form of power, one that helps kids grow into curious, engaged, and empathetic adults. And it shouldn’t belong only to New York’s most privileged students.

Those closing sentences of this essay hit especially hard in the context of the book-banning initiatives sweeping the country. Gonzalez’ focus, however, is something else entirely: the politics of reading curricula in New York City public schools and how one K-6 curriculum, Into Reading, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, seems to be squeezing actual books out of the classrooms of the schools that adopt it. Gonzalez starts by pointing out that the previous pedagogical approach, called “balanced literacy [which] attempted to teach kids to read not through phonics, but by exposing them to books of their choice in order to foster a love of reading” turned out to be a huge failure, given the “appalling literacy numbers” posted by the city’s elementary schools. Into Reading is one of a number of curricula based on “a large body of research finding that learning to read and write well requires phonics, vocabulary development, and content and context comprehension.” The problem, Gonzalez writes, is that instead of “read[ing] and discuss[ing] whole books, [students whose schools have adopted Into Reading]…get [to read instead] a few paragraphs at a time [before being] prompted to answer a question. Reading has been distilled to practicing for a comprehension exam.” Gonzalez goes on to talk about how the school districts where Into Reading has been implemented tend overwhelmingly to be those in “the city’s most heavily immigrant, Black, and brown areas.” It’s worth following Gonzalez’ analysis to see how she ends up at the concluding sentences I quoted above. Fighting book bans is one, crucially important thing, but there are other ways to steer kids away from the kind of democratizing, potentially subversive power that one can claim through a true love of reading. We need to pay attention to and fight against those as well.

§§§

“On Textual Violence: Cultural Imperialism and Monolingual ‘Translation,’” a conversation between Mona Kareem and Yasmeen Hanoosh:

I wanted to take the veil of innocence off of literary translation. The colonial nature of translation is widely discussed in translation theory and translation studies, yet it often focuses on colonial archives or dictionaries, to give some examples. Literary translation, however, has been able to maintain its righteousness and innocence, which is really an extension of white innocence. For a working example, I focused on what is referred to as “bridge translation” whereby a white poet and a native speaker co-produce a translation in which the latter is silenced while used as a bridge. The issues with such phenomenon are many: political, ethical, aesthetic. Yet it goes unquestioned, even encouraged.

As someone who was commissioned by a now-defunct Iranian cultural organization to produce more than one of these “bridge translations” from classical Persian literature into English—though my informants were (long-deceased) English-speaking Persian Studies scholars, not native speakers—I take the questions Mona Kareem raises here very seriously. I will tell the story of how I came to make the translations I have published another time. Here I will say only that I took pains to distinguish in a responsible way the work I did from the work of Coleman Barks and Daniel Ladinsky, whose versions of Rumi and Hafez respectively are deracinating, appropriating, and, frankly, colonizing in precisely the way Kareem alludes to in her use of the term “white innocence.” (I will leave the degree to which I succeeded and failed—because I am sure it’s both—to readers of these works.) Reading this conversation also brought home to me both my own ignorance of contemporary Arabic poetry and the degree to which all poetic cultures, and all efforts at literary translation, confront more or less the same questions, though they may do so at different historical moments and with different cultural and political histories as context. Those differences, I think, are what make room for learning to take place.

§§§

“A Professor Was Fired for Her Politics. Is That the Future of Academia?” by Sarah Viren:

In their analysis, however, FIRE researchers highlighted one specific finding as particularly troubling: that a majority of “sanction attempts” against scholars came from inside the academy — from faculty, administrators or students. It’s a framing of the data that supports a broader conservative argument: that an intellectual monoculture is growing in the academy and is stifling freedom of speech. This view puts FIRE at odds with the American Association of University Professors [AAUP], which has long held that there are limits to what faculty members can say or write and those limits should be determined by the faculty members themselves.

Viren’s article, which is primarily about Maura Finkelstein’s firing from her tenured position at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania for pro-Palestinian statements she made both in and out of the classroom, also takes on the question of how that firing should be framed. The paragraph I’ve just quoted gets at one important component of that question. The politics surrounding Finkelstein’s statements and the various responses to them are by now well-rehearsed, so I’m not going to go into them here except to say that it’s clear to me that Finkelstein’s firing had more to do with what has come in some circles to be known as the “Palestine exception” to free speech and academic freedom than with any actual harm she did to students in or out of the classroom. It matters deeply, though, whether you frame the academic freedom that was violated in this case as an individual right—which is how the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) sees it—or the way the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) does, as a norm that is determined, and the boundaries of which are policed, by the academic community itself. Finkelstein, for example, was fired in spite of the fact that the investigation into her statements, including a review by her peers, determined that they were neither harassing nor discriminatory. Both AAUP and FIRE argue that this was wrong. Importantly, though, as Viren notes, FIRE sees Finkelstein’s case as of a piece with that of University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax, who, after an investigation by her peers, was suspended last fall, with a pay cut, for saying things like “the United States would be better off with more white people and that women are less knowledgeable than men, telling a student that Black people are inferior to white people and publicly discussing the grade distribution in her classes based on race.” It’s hard to imagine Wax’s statements not being directly harmful to students, since they relate explicitly to how she might evaluate student work; and so, at least for me, it’s hard to see the two cases, as FIRE clearly does, through the same lens. There’s a lot more to be said about this, of course, but FIRE’s position is deeply troubling to me, since it opens the door to and justifies precisely the kind of politically motivated, governmental intrusion into academia that we are currently seeing under President Trump.

Four Things To See

Backyard View, Public School in Background, Rulo, Nebraska, c. 1900, by Agnes Winterbottom Cooney

Agnes Winterbottom Cooney (1878-1940) was an American photographer who specialized in cyanotype prints. This photographic process creates a distinctive blue color, which can be seen in her images of landscapes, interiors, and people. Cooney captured the everyday life of her time, showcasing details from architecture to everyday objects, capturing the beauty of simple things and the charm of ordinary scenes. Her work is a unique window into the past, offering a glimpse into the world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

§§§

The First Day of School, Jean Baptiste Vanmour, c. 1720 - c. 1737

A mother, accompanied by a group of women, brings her daughter to school for the first time. That the women are Turkish can be seen from their colorful clothing and the yellow slippers that only Muslims could wear, according to sumptuary laws (dress codes). A servant carries the girl’s embroidery frame. Needlework was a favorite pastime of women in affluent Turkish circles. Women held in slavery did the household chores.

§§§

The Writing School, Utagawa,

Toyokuni, 1769-1825 (Printmaker), Eijudo (Japanese, active 18th century) (Publisher)

§§§

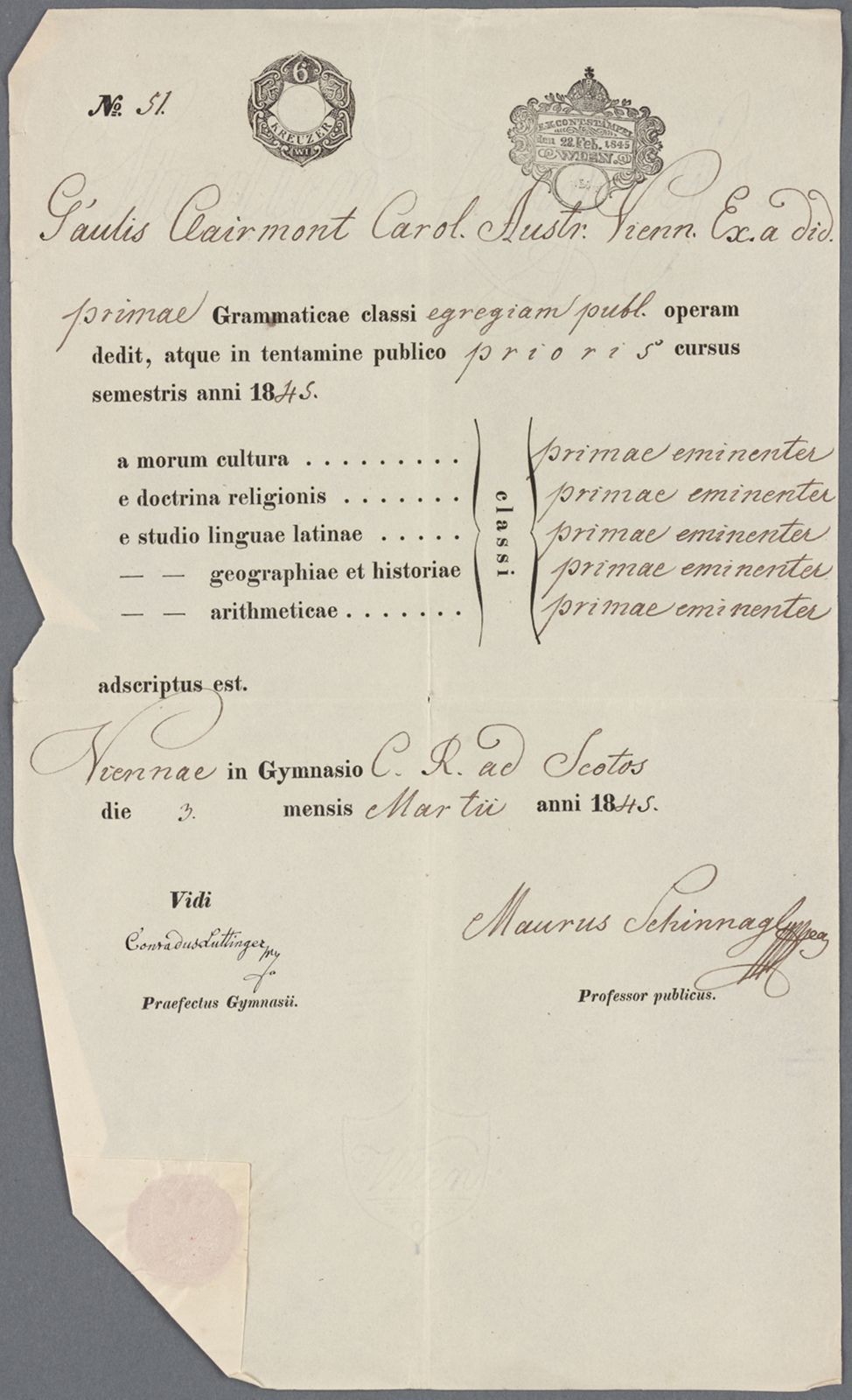

The Report Card of Charles Clairmont, March 3, 1845

Four Things To Listen To

Abel Selaocoe - Ka Bohaleng / On The Sharp Side (Later with Jools Holland)

§§§

Abel Selaocoe & Bantu Ensemble 'Les Voix Humaines / Tsohle Tsohle' Live at KOKO

§§§

Hugh Masekela, Thuma mina

§§§

Miriam Makeba - Pata Pata (Live at Avo Session, Basel, 2006)

Four Things About Me

Back in the mid-to-late 1980s, when I was getting my MA in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), I worked part time in the Writing Center—then called The Writing Workshop—in the English Department from which I just retired. Since I was the only TESOL-qualified person there, most of the students I helped with their writing were second language learners. I remember one in particular, a woman from Iran, who was failing her English composition class and whose writing, it was clear from start, would not improve enough by the end of the semester for her to pass. As we discussed her situation, she revealed to me that she would lose her visa if she failed and that, if she was forced to return to Iran, she would face certain arrest and likely execution for her political activities in opposition to the still-relatively-new Islamic Republic. I don’t remember the details of how she obtained the visa, but I know I had no reason to doubt her, so I shared this information with her professor. He agreed to give her a minimal passing grade, though not without expressing to me, as if he held me personally responsible, his resentment that politics was intruding on the academic integrity of his classroom. What I remember most about this woman’s story, though, is the young man—he was either a Quaker or a Mormon; I don’t remember which and I have no memory of how he became involved with her—who offered to marry her so she could stay in the United States and eventually apply for citizenship. I don’t recall if he made that offer after they’d already started a relationship or before—my gut tells me it was before—but I know they did start seeing each other. I have no idea what happened to them, but I hope she was able to stay here and, if they did get married, I hope that they are still married and happy and living a fulfilled and fulfilling life.

§§§

The strangest excuse a student ever gave me for not getting their work in on time came from a young woman who explained to me that her boyfriend, who’d been serving in Iraq, would be coming home soon. I thought she was going to tell me that she’d been so excited and so involved with preparations for his homecoming that she’d let the assignment that was due fall by the wayside. Instead, she told me this. She’d been unfaithful, once, with a guy she knew from high school. Unfortunately, her enemies from high school, had somehow videoed that encounter—I don’t remember if the guy she was with was in on it—and they were blackmailing her. Her family, she said, was very wealthy and this group threatened to show her boyfriend the video if she did not steal for them some of her mother’s extremely valuable jewelry. I couldn’t imagine her making up a story like that to get an extension on a single paper, so I gave her the extension she was asking for, but, while I have a sense that she eventually disappeared from the class, I have no clear memory of what happened after that.

§§§

The most audacious request I ever got from a student came from a guy who showed up on the last day of class. He’d been doing the work till about a third of the way through the semester and then he just disappeared. I emailed him a couple of times to find out what happened, but he never responded. There he was, though, on the last day of class, waiting till everyone else was gone to speak with me. When I asked him where he’d been, he told me that he’d been arrested, along with some of his friends, for assaulting someone; that he’d been going to court, meeting with his lawyer, and dealing with other things related to the incident, which was why he hadn’t been in class. He then told me that because the damage he and his friends had done to the person they assaulted was so extensive he was almost certainly going to end up doing some time in jail. I could see the fear-bordering-on-panic in his eyes as he told me this, so, because he’d been a decent student till he stopped coming, and because I didn’t have the heart to be cold in the fact of his very real fear and just fail him outright, I offered to give him an incomplete for the class so that he could tell the judge that he planned to finish his coursework while he was serving his sentence. He looked me straight in the eye and without missing a beat said, “Actually, I was kind of hoping you’d give me a B.” I was, as you might imagine, stunned. I pointed out that he had in fact already failed the class and that I was doing him a favor by offering the incomplete. Then I asked what made him think I would give him a B. He said, without a hint of irony or any sort of self-awareness in his voice—and this is a direct quote—“I was hoping you’d do me a solid.” Needless to say, he failed the class.

§§§

The most disturbing encounter I ever had with a student—and please consider this a trigger warning if you’re someone who needs one—came very early in my career, before I was granted tenure. I was teaching a developmental writing course in which I’d asked my students to write a fable. We were sitting in a circle so those who wanted to could share what they’d written and the rest of us could respond. Setting aside the poor quality of the writing, I was impressed with imaginative effort at least some of my students had made. There was, for example, a modernized version of Little Red Riding Hood, set in an upper class neighborhood with the most sought-after senior boy in the local high school taking the part of the wolf. Another student conceived of a gender-reversed Sleeping Beauty, in which Princess Charming turns out to be the homeless woman who sleeps in the park. I was about to move on to the next part of the lesson when a young man who’d told us at the beginning that he didn’t want to share his story said that he’d changed his mind. His story concerned a drug dealer whose organization a female narcotics agent had been able to infiltrate by befriending the dealer’s girlfriend. When the girlfriend found that her new friend was, in fact, a narc, she informed her boyfriend, who killed the agent and, as thanks, gave his girlfriend “the literal fuck of her life, pounding away until she was no longer breathing.” The story ended with a description of the lavish funeral the dealer gave her.

I will at some point write more about this encounter. Here, I will cut to the conversation Warren and I had after class. “Now that everyone else is gone and you don’t have to say the right thing,” he said—and these were his exact words; I wrote them down immediately afterward—“be honest. Wouldn’t it feel great to take some slut to a hotel and then meet your buddies later and tell them you’d killed her with your dick?” I told him no, but before I could say anything else, he went on, “Sure, maybe now that you’re older and you can’t get it up like you used to”—I was all of twenty eight—“but when you were younger, when you were an undergraduate, say, wasn’t fucking something you did so you could share it with your buddies, and impress them, and wouldn’t they have worshiped you if you told them you’d fucked a girl to death?” I decided that a monosyllabic answer was the best way to respond, since I knew I was not going to persuade him otherwise, so I said no again and went back to packing my things.

Warren waited a few seconds and, when he realized I wasn’t going to say anything else, walked out of the class, muttering something under his breath of which I think I heard the words “pathetic,” “excuse,” and “man.” He did not come back to class after that, which might very well have had nothing to do with our conversation, but it’s hard for me not to think that it did. In the end he officially withdrew from the class and I never heard from him again.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion