Four Things To Read

Put It On Record: A Memoir-Archive, by Sokunthary Svay:

It’s been over a dozen years since my postpartum depression but when summer begins in New York City, I still feel the ghost of that experience weighing down in the oppressive humidity. It’s one negative remnant of the first few months of my son’s life, although I have one good memory to counter that. One weekend afternoon at the close of summer, shortly after I sought help, my husband and I pushed our baby in the stroller on a neighborhood walk. As we got closer to home I could suddenly see the leaves on our tree with clarity. Perhaps it was the medication taking its course, or my first feeling of hope since my son was born, but that afternoon I felt the sun on my side for the first time.

The story Svay tells about emerging from her postpartum depression is in many ways a mirror of the story she tells about coming to terms with being an immigrant refugee in the United States and a survivor of the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal dictatorship in Cambodia; and it is the tension between those two experiences that gives this book its power. In each case she is estranged from herself by a radical disruption in her life, a physical/emotional/psychological experience that shatters her sense of self, and, in each case she needs to find a way not back to wholeness, but to reintegration of the disparate parts that results in a very different experience of what it means to be whole. In their broad outlines, the stories she tells have been told before, by other women, by members of other immigrant communities. What makes this memoir-archive so interesting, at least to me, is how Svay locates what I am calling the reintegration of her self firmly within her search for a way to give music a meaningful part in her life as an artist. It’s a journey well worth taking with her.

§§§

“In The Bedroom,” by Yehudis, translated from Yiddish by Jordan Finkin:

“Mirel, are you being serious? I don’t understand that kind of love. A young girl doesn’t love that way. She loves spiritually. Physical love comes next, eventually, unnoticed. A young girl can’t be the object of suspicion . . . I remember I was still young. My love for Dovid was an accident. Were I to meet a woman with his qualities, I thought, I would also love her in earnest . . . I loved listening to him talk for hours on end. He understood everything so cleverly, so deeply. My own desire was to understand Dovid, to be like him.”

These lines, spoken by Gine to her friend Mirel while they are laying in separate beds, capture nicely the tension this short story explores between the desires these women feel and the social strictures within which they have to live. The story was published in 1908 in what Jordan Finkin calls in his brief introduction a “Passover collection,” and, indeed, another tension in the story is that between the meaning of Passover as a holiday that celebrates freedom from slavery and the lack of freedom these women feel in their own lives. Yehudis is the pen name of Rokhl Bernshteyn(1869–1942), was an important voice in Yiddish literature, though she is virtually unknown today. Finkin’s translation of this story is a worthwhile and, I would say, necessary attempt to give her work a renewed and serious attention.

§§§

“Inside New York’s Statue of Liberty,” by Melech Ravitch, translated from Yiddish by Daniel Kraft:

I am a man of flesh and blood and bone,

my soul is love, laughter, and tears —

and you? Woman, empty iron giant,

with a torch raised in your hand,

you are a golem-woman with tin skin

mounted upon a skeleton of steel — —

your tin lips have never kissed bread.

Your iron ribs have never rocked a man in bed,

and — — I love you with a young love, fiery and tender,

for thirty years of youth and manhood I have yearned for you,

awaiting your first glance.

Melech Ravitch was the pen name of Zekharye-Khone Bergner (1893–1976). A poet, essayist, playwright, and cultural activist. Ravitch was born in Radymno, eastern Galicia. He was raised in a secular home, where the primary languages were Polish and German. He began to write poetry in Yiddish under the influence of the 1908 Czernowitz Conference, an international conference on Yiddish language and its role in Jewish life. He was also widely traveled, living in Australia, Argentina, Mexico, and Montreal, where he died in 1976. This poem on the Statue of Liberty is interesting, particularly in contrast to Yehudis’ story, for its frankly sexual address to the statue as a symbol of liberty. Here, in the United States of the 21st century, it’s hard not to hear the ending of the poem as Christological, but I doubt very much that’s how Ravitch meant it. It’s more likely that he meant it as an expression of hope for the United States as “the land of the free.”

§§§

“In 1975, Gay Moms Rarely Got Custody. So She Took Her Child Underground,” by Sarah Diamond:

The rescue — or kidnapping — played out entirely in private and was known only to the people involved. It also occupies a small but meaningful place in the history of the gay rights movement. Georgette DuBois was part of an underground group of lesbian mothers who worked together to take and hide their children because most courts considered gay parents unfit.

I’d heard, of course, about underground abortion networks, and about underground networks organized to help women and their children escape abusive husbands/boyfriends, but until I read this article, I’d never heard about the underground network formed to kidnap—legally that’s what it was; though I am sure that “rescue” was also not uncommonly an accurate term—the children of lesbian mothers to whom the courts homophobically refused to award custody. The article tells the story of Georgette DuBois, who married Raymond LaRosa when she was 19. They had a daughter, Kara. At some point, Georgette fell in love with a woman. As Georgette remembers it, after telling her that she should go be with a woman if that’s what she wanted, she and Raymond got along and managed a kind of informal joint-custody arrangement, but then Raymond took Kara from Pennsylvania, where they all lived, to Michigan. This was in 1975, just two years after the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders, and the norm was still to see lesbian mothers as a kind of danger to their children, which was why Georgette, after consulting with lawyers who advised her that the only way she would get her daughter back was to “go underground,” conspired with other women to take her daughter back from Raymond. The story is worth reading in its own right, but it made me think about how culturally determined the assumptions about who should get custody of children in cases of divorce are. When my parents got divorced, the default assumption was that children would stay with their mother; in Korea, when I was there in the late 1980s, the default was that children stayed with their fathers. The article made me think as well —I’m setting aside for the moment what this issue looks like when it comes to gay parents—about how those assumptions are an artifact patriarchy and how patriarchy makes men and women default adversaries even when it comes to questions concerning their own children. If the right has its way—and we are inching there in bunches of inches—we will be going back to a society in which the law sees things more or less as it did in the 1970s, if not earlier, and the only people that is good for, ultimately, are the rich, mostly white men whose interests that kind of society is most efficiently organized to serve.

Four Things To See

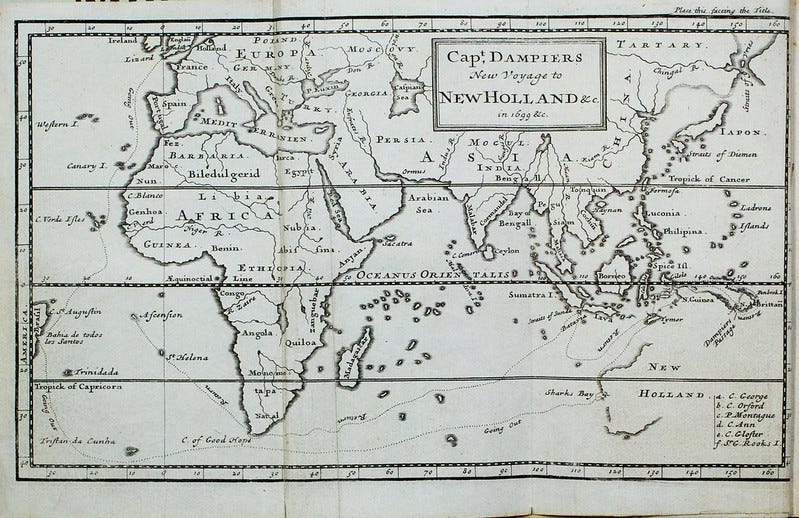

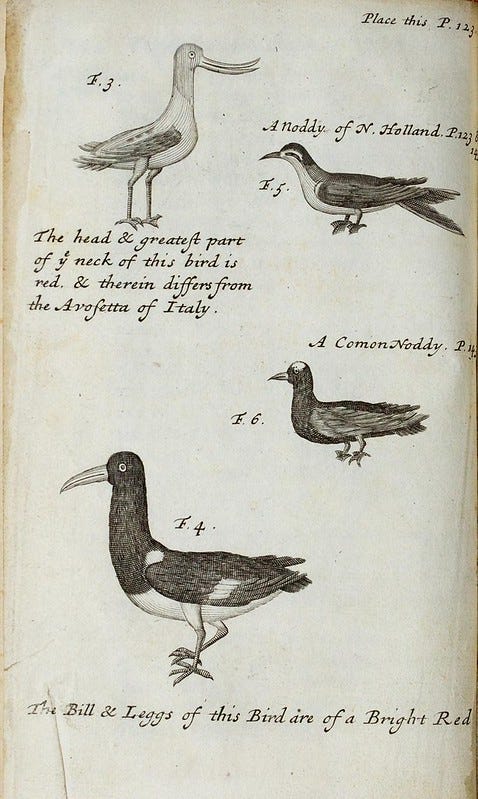

All illustrations are from A Voyage to New Holland, published in 1699, by William Dampier, 1651-1715.

William Dampier

§§§

A Voyage to New Holland (Australia)

§§§

Fish From a Voyage to New Holland

§§§

Birds from a Voyage to New Holland

Four Things To Listen To

Two very different jazz poets, each very much worth hearing.

Aja Monet - Black Joy

§§§

Aja Monet - Why My Love

§§§

Barry Wallenstein - Eventually

§§§

Barry Wallenstein - Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Four Things About Me

My Masters Degree is in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, but the coursework in my program focused more on applied linguistics than on pedagogy. One of the subjects we studied, though I don’t remember now if it was an entire course unto itself or one unit within some other class, was linguistic fieldwork methodology, specifically in our case the strategies by which one can begin to map out the syntactical, semantic, and sociolinguistic structures of a language you do not speak and may never had heard before in your life. There was a woman from Burundi in our class and she agreed to be our Kirundi informant. The only thing I remember with any certainty about Kirundi is that it has sixteen noun classes. Noun classes are categories of nouns to which specific grammatical rules apply, like, for example, masculine and feminine nouns in languages like Spanish or Hebrew, with which the corresponding masculine or feminine forms of verbs and adjectives must be used. I’m not sure if this example, which has nothing at all to do with gender, comes from Kirundi, but I distinctly remember our professor giving an example in which nouns which referred to objects that were flat and round and nouns that referred to spheroid objects belonged to two different noun classes. Intellectual puzzles like that fascinated me and, if I wasn’t sure that teaching was what I wanted to do, I might very well have pursued a PhD in linguistics instead.

§§§

The other reason noun classes fascinated me so much had to do with the reading and thinking I was doing at the time about gender. I’m not going to try to reconstruct precisely what I was reading, but I remember having arguments with the way some of the feminist texts I read seemed to talk about manhood and masculinity as unchanging fixtures of the patriarchy within which anyone born into a male body was trapped. At the heart of these arguments was the fact that these same texts would sometimes wax poetic about all the different ways in which women could express and explore womanhood. I did not have a very sophisticated critique of what I perceived, and I don’t know if I ever said this aloud at the time, but I didn’t understand why, if a culture could distinguish in language between objects that were round and flat and objects that were spheroid, it couldn’t also distinguish between and among different ways of living in and expressing the identities of male and female bodies. I didn’t understand, in other words, why gender could not be a spectrum. Or at least a spectrum of sorts. I still divided the world into two genders, but I started to be able to imagine a world in which, within those two categories, there could be a very wide range of variation. I don’t remember if I ever said that out loud. Frankly, it felt to me so “out there” that I couldn’t imagine anyone taking it seriously.

§§§

Back in the 1990s, I published an essay about pornography called “Inside The Men Inside Inside Christy Canyon,” the concluding paragraph of which read in part: “I want a heterosexual pornography in which…male trust is eroticized, in which the places we have not been touched, the places it is in the interest of male dominance to keep hidden, are…brought into knowledge…For when the touch of sex is a touch that holds but does not violate, a space is created in which the life of one human being can co-exist in complete freedom with the life of another. This is what the sex in heterosexuality could be.” A friend who read that essay characterized it as an attempt “to queer” heterosexuality, which—though I would not have used that language at the time—I think it was. I thought about this as I finished writing the previous paragraph because I think, intellectually at least, the impetus to write “Inside The Men Inside Inside Christy Canyon” was partially rooted in the thinking about gender that learning about noun classes inspired.

§§§

Life choices always turn “what could have been” into “what might have been.” I have often wondered, for example, how my professional and creative life would have been different if I’d chosen to pursue a PhD in linguistics. I have no regrets about the choice I did make, but when I think back about why I made that choice—I was tired of being a student; I was ready to get a job and start living my life; and I wanted to travel and a TESOL degree would make that possible, largely on someone else’s dime—I am aware that I cut myself off from what I might have written and published and done if I’d pursued the academic and career path indicated by the three above paragraphs.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion