Four Things To Read

Why Everything Israelis Think They Know About Iran Is Wrong, by Orly Noy:

“In Israel, the voices being amplified are those of Reza Pahlavi [the exiled Iranian crown prince] and his supporters — people with no real credibility or influence inside Iran,” he told +972 Magazine in an interview. “In the past 10 years, a lot of money has been invested in building up his image, and suddenly he’s gone from being seen as a sixty-something slacker to a crown prince with a whole kingdom behind him. This is a reality that exists only in ‘Tehrangeles’ [a nickname for parts of Los Angeles with a large Iranian exile community] and in the margins of the current U.S. administration,” Sternfeld added. “And it’s the only one Israelis are hearing.”

Noy is quoting here Professor Lior Sternfeld, who teaches the modern history of Iran at Penn State University. The rest of the article is taken up by Noy’s interview of Sternfeld, which is worth reading for its perspective on how the Israeli government, and to some degree also parts of the US government, are shaping perceptions of Iran and how the resulting misperceptions will ultimately do more harm than good.

§§§

Breaking the Israeli Book Curse, by Amy Klein:

Last year, my agency must have gone down about 70 percent in sales. We’ve lost many clients and friends. I have not sold an Israeli literary project since October 7, other than someone whose voice has already been out there. There are Israeli writers who have succeeded—Dorit Rabinyan, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen—and have faithful readerships, created when there was support from publishers to do so. A readership for Israeli writers has been created, but publishers are not buying enough new Israeli voices to meet that audience. There’s a fear that the next generation of Israeli writers are going to remain unknown around the world. I am also getting 10 new queries a week from American Jewish writers who can’t work with their agents anymore, or their agents won’t work with them. It’s heartbreaking for American and European audiences, because I don’t think the readership is the problem. It’s the gatekeepers of the publishers that are not letting them in.

Klein interviews here Deborah Harris, a literary agent based in Jerusalem, whose agency has represented “the translation and dramatic rights of 140 Israeli and Jewish writers in more than 50 countries and also acts as a co-agent in Israel for more than 230 international publishers and literary agencies.” It is not surprising, though it is disturbing, that people would boycott Jewish and Israeli writers given what is going on in Gaza. The discussion around that issue, however, is pretty familiar and so I am simply going to note it. What I found particularly interesting about the interview—and this is the reason I’ve decided to include it here—was Harris’ response to Klein’s question about “recent shifts, for better or worse,” in connection with the Israeli publishing industry: “I just got the current list of international authors who won’t be published in Israel, novelists like Isabel Allende and Fredrik Backman.” In other words, decisions are being made that will keep the work of writers like Allende out of Israel. The interview is worth reading and discussing. It raises some thought-provoking questions about how writers and the publishing industry ought to respond to situations like the one in Israel/Palestine.

§§§

The False Narrative of Settler Colonialism, by Adam Kirsch:

Although Israel fails in obvious ways to fit the model of settler colonialism, it has become the standard reference point because it offers theorists and activists something that the United States does not: a plausible target. It is hard to imagine America or Canada being truly decolonized, with the descendants of the original settlers returning to the countries from which they came and Native peoples reclaiming the land. But armed struggle against Israel has been ongoing since it was founded, and Hamas and its allies still hope to abolish the Jewish state “between the river and the sea.” In the contemporary world, only in Israel can the fight against settler colonialism move from theory to practice.

I wish Kirsch had chosen a framing for this essay other than a critique of settler colonialism because he makes some very good points. Those points, however—many of which have to do with the ways that critics of Israel fail to uncouple the rhetoric of their criticism from historical antisemitism—get lost in his desire to “rescue” Zionism from the clutches of settler-colonial theorists. So, for example, when Kirsch critiques claims like this one by Jamal Nablusi, that “Palestinian Indigenous sovereignty is in and of the land,” for having roots in the same 19th century German nationalism that ultimately “degenerated into the blood-and-soil nationalism of Nazi ideologues,” he conveniently elides the fact that Zionists made the same kinds of claims for the Jewish connection to Israel and that those claims continue to be made by those encouraging Jews at least to visit, if not to settle in Israel. Certainly I was told when I was younger that the only place I could be authentically Jewish, whatever that means, was in the “authentic” Jewish homeland, the State of Israel. There are similar moments throughout the essay, but I think it is worth reading nonetheless. First because it’s important to recognize those moments for what they are, but also because I think his analysis of those moments when anti-Zionism/anti-Israel critiques bleed over into antisemitism is worth wrestling with.

§§§

History Lesson, by Laleh Khalili:

The best corrective to Kirsch’s attempt to dismiss the concept of settler colonialism as a shallow fad is a substantive discussion of the actual historical process—especially the colonization of Palestine, as understood from the vantage of its victims. While some colonial systems depended on the exploitation of local labor (sometimes via local intermediaries), the term “settler colonialism” refers specifically to those colonies where, as historian George Fredrickson wrote in The Arrogance of Race, settlers “exterminated or pushed aside the indigenous peoples” and “developed an economy based on white labor.” (In practice, this meant developing settler workers’ skills and lifting their standard of living while de-developing and de-skilling the remaining Indigenous workers, whose labor the colony continued to mine.)

Khalili’s tone in this review of the book from which the Kirsch essay I linked to above was adapted, On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice, is one of withering contempt. A similar, but less venomous tone informs Samuel Hayim Brody’s review in The Boston Review. Both are worth reading. They confirmed my own sense that whatever is of value in Kirsch’s analysis—and I have read only the article, not the book—is overshadowed by his desire to defend Israel and Zionism against what he considers the depredations of settler-colonial theory and his need, therefore, to argue that this theory is, at best, enabling of those who would like to remove the Jews from the face of the earth.

Four Things To See

Torah Finials (Rimmonim)

From The Jewish Museum: In a publication from 1931, this pair of finials (rimmonim) is described as being in one of the two Kassel synagogues, the second of which the Nazis set on fire during Kristallnacht in 1938. Nothing is known of the items’ provenance between 1938 until 1970, when the finials were purchased from a dealer. According to their inscriptions, the finials were “a donation of Rabbi Zelig, son of Rabbi Feis of blessed memory, for the Torah scroll of the Benevolent Society in the year [5]559 [1798/99].” (This information is from Masterworks of the Jewish Museum, by Maurice Berger, et al. For more information, go to the item’s page at The Jewish Museum.)

§§§

Rolled Sheet with a Magic Inscription in Either Hebrew or Aramaic

From The Getty Museum Collection.

§§§

A Parade Entering the Old City of Jaffa, Palestine (now Tel Aviv, Israel)

This is an unfinished study by Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900). This is the text from the Smithsonian’s website: “In the foreground, several figures dressed in colorful draped clothing and cloth headwear cross a stone bridge while playing drums and waving green-and-red flags. A large patch of grass comprises the middle distance at center. At upper left, a circular minaret towers over the other buildings, while the Spanish style belltower of St. Peter's Church is visible in the background at center. At right, the remainding skyline is rendered only in graphite, and shows multiple domes and towers.”

§§§

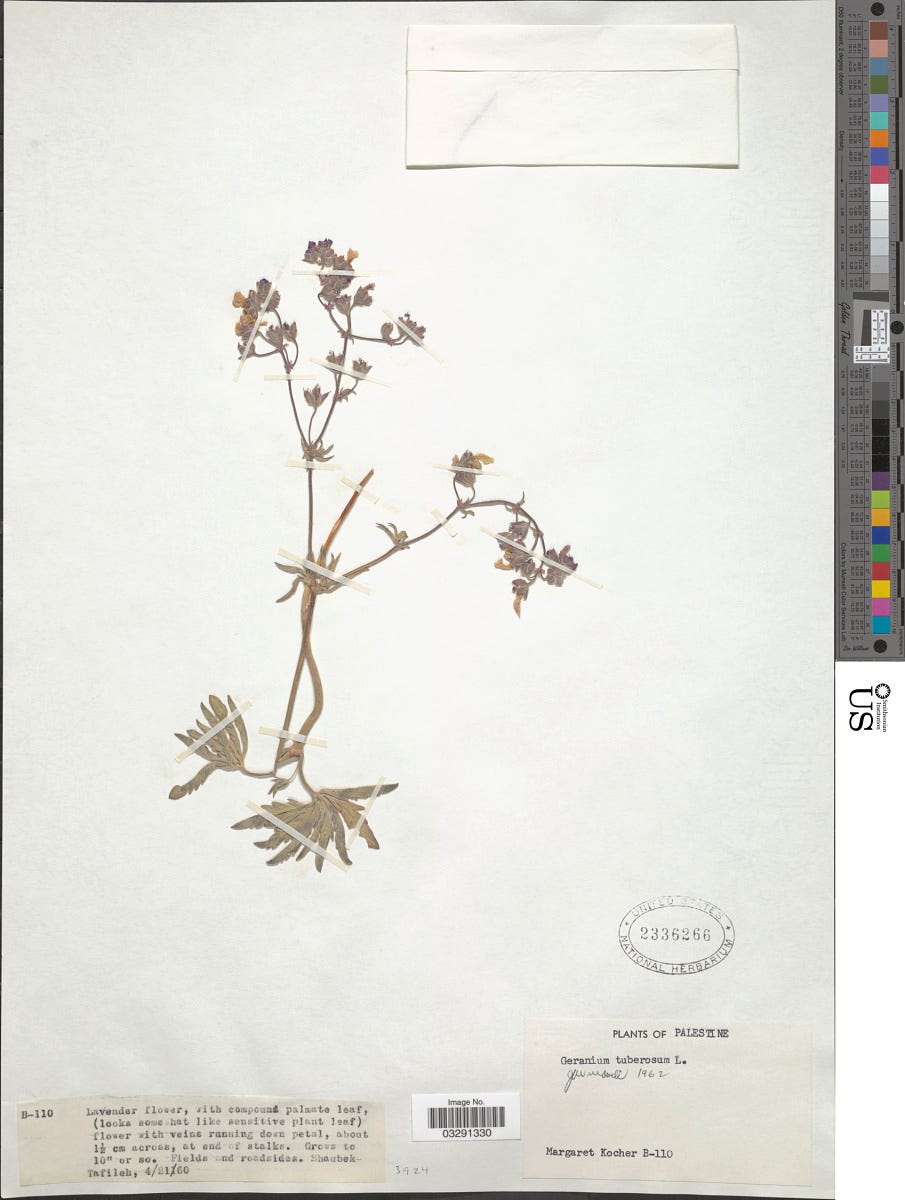

Geranium tuberosum L.

From the Smithsonian. This specimen of geranium tuberosum was gathered in 1960 by Margaret Kocher in Shaubek-Tafileh, Palestine/Israel. (The museum records give both place names.)

Four Things To Listen To

Biosphere - Time of Man

§§§

Emel - Massive Will

§§§

Sama' Abdulhadi feat. Walaa Sbait - Well Fee

§§§

Youmna Saba - Ba'oud

Four Things About Me

When I was in graduate school, I lived in a basement apartment in a house not far from campus. The owner of the house, a single woman with two children, was named Linda. We got along well and even became kind of friendly. She began inviting me to sit and chat when I went upstairs with her rent check. She even asked me once or twice to keep an eye on her kids when she had to make an emergency run to the grocery store or some such thing. There was nothing even remotely flirtatious in our relationship. At some point, she started dating a man whose name, I think, was Ray. I met him once or twice and he seemed like a nice enough guy. After a while, she invited him to move in with her. Ray didn’t move in right away, however, and it was clear from the way she began to keep her distance from me, and from the suspicious way he looked at me whenever he saw me, that my presence was at least one reason why. Linda wouldn’t tell me this to my face, however. One day, I found a note taped to my front door that I would have to leave by the end of the month and nothing more, which hurt my feelings a bit, given that we’d become a little more than just landlord and tenant. Thankfully, it was also the end of the semester in which I received my MA, so I didn’t need the apartment anymore. I remember having to make two or three trips back and forth to my mother’s house in what my friends back then called my “sporty red station wagon”—it was a Chevy Malibu—and leaving Linda a very obnoxious note in an empty, but very messy apartment. I don’t think I mentioned Ray in the note, but I still wonder every so often if the problem he had with my renting that apartment ever became a problem in his relationship with Linda. I hope not, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it did.

§§§

When I lived in Korea, I became lovers with the woman who lived downstairs from me. She spoke more English than I did Korean, but neither of us spoke the other’s language well enough that we could have anything other than the most cursory conversation without my bilingual dictionary. I told the story of our relationship—at least as I understood it back in 1999; I think I’d tell it slightly differently now—in an essay in Salon.com, but what I just remembered now, after writing the above recollection, is that there was a Korean man who somehow knew she and I were together. I have a vague memory of him approaching me in a park not far from where I lived and striking up as much of a conversation as I was able to have, though I don’t remember what it was about. He seemed friendly enough, but then, a few weeks later, I could hear him pounding on my friend’s door, yelling something about the migook saram, the American, and the question ooweh, why, over and over and over again. My friend started screaming back, her voice muffled, though she was speaking so quickly, and so clearly in anger, that I doubt I would have been able to understand anything she said even if I’d heard every word. I stepped out of my apartment and stood at the top of the staircase, not knowing what to do except, at least, to be a witness and maybe try to stop him if he became violent. My friend’s door was closed, which was why her voice was muffled, but I continued to stand there, watching, until, when he stopped banging on my friend’s door for a few moments, the man must have sensed my presence. In a scene that might have come from a movie, he locked eyes with me then looked at my friend’s door— she’d gone quiet in response to his own silence—then he looked back up at me, made a face I did not know how to read, and walked the four flights down to the building’s exit. I knocked on my friend’s door, but she did not answer, not even to tell me to go away. So I left her alone. The next time I saw her, I tried to ask her about what happened, but all she would say was that it was not my problem and that I didn’t need to worry about it. We never spoke about the incident again.

§§§

One of the oddest experiences I had in Korea happened when I was sitting by myself near a fountain on I-don’t-remember-which-floor in the Lotte World Mall. A little girl, not much older than five or six, who’d been watching me from where she was sitting with her mother on the other side of the fountain, climbed down from her mother’s lap, walked up to me, and held her arms out for me to pick her up. Looking over at her mother, who smiled at me, I lifted the girl into my own lap. She then took one of my hands and turned it palm up, reached into the fountain and let a few drops of water drip from her wet hand onto my dry one. She stayed with me not more than thirty seconds longer and then motioned for me to put her down. When I did, she walked back to her mother, who smiled at me again as she took her daughter’s hand and left. That was it. I never saw either of them again.

§§§

In the apartment complex where I lived in Seoul, in a part of the city known as Jamshil, a group of children would usually be playing outside when I left for work. Whenever they saw me, they would follow me from behind, yelling and posting and laughing with delight as they called out, “Migook saram! Migook saram imnida!” (An American! It’s an American.) At first, not really knowing how to respond, I ignored them; but as I grew more familiar with the culture and learned a little bit of the language, a game developed between us. At some point, I would turn around and ask “Odioh?” (Where?) They would point at me and respond “Yogioh!” (Here!) We’d go back and forth like this a couple of times and then I would say, in English, “I have to go to work,” and, as I turned to leave, they would say, in English, “Goodbye!” Eventually, though I have no idea why, the kids stopped being there in the morning. I missed seeing them and I missed playing that game with them.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion