Writing News

Last month I started blogging for my publisher, Fernwood Press. We’re calling the blog Learning to Love the Questions, and it will be about the relationships between and among poetry, politics, and (non-institutional, non-doctrinaire) spirituality. I’ll be posting once a month. (You can read the introductory post here.) If you’d like to subscribe so you receive the posts by email, you can do so on the blog’s home page. I’ll also link to new posts here in Four By Four. I hope you’ll consider reading.

Four Things To Read

I Teach Creative Writing. This Is What A.I. Is Doing to Students., by Meghan O’Rourke:

I’ve spent decades writing and editing; I know the feeling — of reward and hard-won clarity — that writing produces for me. But if you never build those muscles, will you grasp what’s missing when an L.L.M. delivers a chirpy but shallow reply? What happens to students who’ve never experienced the reward of pressing toward an elusive thought that yields itself in clear syntax? This, I think, is the urgent question. For now, many of us still approach A.I. as outsiders — nonnative users, shaped by analog habits, capable of seeing the difference between now and then. But the generation growing up with A.I. will learn to think and write in its shadow. For them, the chatbot won’t be a tool to discover…but part of the operating system itself. And that shift, from novelty to norm, is the profound transformation we’re only beginning to grapple with.

O’Rourke’s question is urgent. It is, in a way, a version of the question I ask implicitly below, in Four Things About Me, when I talk about the difference between writing a letter and communicating by email or text messaging, except that an AI could, in theory, write those emails and messages for you. Especially worth paying attention to is the way O’Rourke traces her relationship with the AI. After talking about the ways she learned to use AI to make her life easier, she says that “[w]ithout my intending it, ChatGPT quickly became a substantial partner in shouldering the mental load that I, like many mothers an women professors, carry[:] ‘Easing invisible labor[.]’” She found herself “writing warmer emails simply because the logistical parts were already handled.” She “had time to add a joke, a question, to be me again.” Then, she began to notice “a strange emotional charge from interacting daily with a system that seemed designed to affirm” her. When she asked ChatGPT about this, after asking it to talk to her about her own poetry, which she says she found oddly soothing, the AI responded that she was feeling that way because it was “mirroring” her, essentially producing, as O’Rourke characterizes it, “a version of myself that experienced no anxiety, pressure or self-doubt.” All of which are necessary parts of the process of “pressing toward an elusive thought [until it] yields itself in clear syntax.” O’Rourke has written an important essay that at least begins to make visible the profound transformation that AI is in the first stages of bringing about in our society and culture.

§§§

The Rise of AI Will Make Liberal Arts Degrees Popular Again. Here’s Why, by Jessica Stillman:

From 2012 to 2020, the number of students majoring in subjects like English and history declined 46 percent at Ohio State. At Tufts, Vassar, and Notre Dame, enrollment in liberal arts majors was down by half. Boston University saw a 42 percent decline. At SUNY Albany the situation was more dire—interest in these degrees fell by three-quarters…[A] lot has changed in two years, [however,] including the stratospheric rise of AI. Now a few lonely but intriguing voices are arguing this is one trend line that’s about to reverse. The AI revolution will bring liberal arts majors back from the verge of death, they say.

Stillman makes here an argument that I have heard before, that the so-called “soft skills” one learns through studying the humanities—empathy, critical thinking, the ability to navigate and negotiate difference—are, contrary to what many think, also truly valuable business skills. The form in which I always heard this argument, in which I have often made it myself, went something like this: Businesses can teach you their business; they don’t want to have to teach you how to write or think for yourself. That this logic did not persuade many in higher ed is evident in the the New Yorker’s bold 2023 declaration that the English Major was dead. I find very interesting, therefore, the contrast between what the AI and business experts Stillman quotes have to say—essentially that, in an “AI-filled future,” the most valuable skills are likely to be those rooted in curiosity, empathy, and “the ability to deal with the messiness and unpredictability of people”—and what O’Rourke described, though these are my words not hers, as her AI’s flattening of precisely those qualities. This difference may very well result from the fact that Stillman’s is a business perspective—her piece was published in Inc. after all—while O’Rourke was in some sense writing in opposition to a bottom-line mentality. To me, assuming the prediction in Stillman’s title comes true, the question is which perspective will win out in shaping the courses of study that liberal arts students will pursue.

§§§

“Food Has Become a Memory”: My Hunger Diary in Gaza, by Sara Awad:

My mom baked eight pieces of bread, one for each of our family members, and each one of us chooses the way to eat it. For me, I choose to separate it into two portions — the second is for dinner. Very small portions for a person who does not eat enough for months. And we do not know when the next bread will come along.

Back in January of last year, I posted a poem I wrote called “The People of Gaza Keep Dying.” As an epigraph, I quoted Yara Asi, the author of How War Kills, from a Jewish Currents article by Maya Rosen, “The Epidemiological War on Gaza:”

You don’t need overt bloodshed to cause significant violence that ends people’s lives. Many people will die unnecessary deaths due to deprivation.

Awad’s essay brings the reality of Asi’s statement home. As I read it, I could not help but also think of Leyb Goldin’s story/essay—today we would probably call it autofiction—“Chronicle Of A Single Day,” which details a single day in the life of someone in the Warsaw Ghetto who is, essentially, dying of hunger. Goldin was born in Warsaw in 1906. He joined the Bund (the Jewish Social Democratic Party in 1936) and be became active before World War II as a writer and translator. During the war, he wrote for the Bundist underground press. “Chronicle Of A Single Day” was found in Emanuel Ringelblum’s Warsaw Ghetto archives and was published for the first time in 1955. While my source says Goldin died of starvation in the Ghetto in 1942, other sources say he died in the great deportation that year from Warsaw to Treblinka. Either way, “Chronicle Of A Single Day” makes the reality of starvation even more viscerally present than Awad’s piece. To be honest, though, I hesitated about making the connection between the two pieces in the way that I have. It too easily plays into the hands of those who insist on equating Israel with the Nazis, a facile comparison that, because it goes much further than pointing out that Israel is using some of the same methods that the Nazis did, always has, intentionally or not, an antisemitic subtext. it is also a comparison that, intentionally or not, elides the fact that starvation has been used as a weapon of war for a very, very long time. I decided to share Goldin’s piece with you nonetheless because I think this is an important connection to make, not only because Goldin was Jewish and Awad is Palestinian—though that specificity also matters quite a lot—but because their very similar suffering represents a shared humanity that is not abstract, that is rooted in the physical facts of their bodies, of our bodies, and what those bodies need for us to survive. Any call for or expression of solidarity that is not rooted in those facts is ultimately hollow at the core.

§§§

Mushroom as Metaphor, by Maria Pinto:

Fungi are mysterious, ubiquitous, ancient, and cunning. They do some of the planet’s humblest work just as industriously as they do what we consider its loftiest: from decomposition and rot, through bolstering our crops, to helping us heal psychic wounds. For better and worse, their lifeways combine with how little we understand them to make the perfect substrate for our experiments in self-image. Over the past forty years of my own lifetime, we’ve cast them as bringers of the apocalypse and saviors of Earth—not bad for a kingdom of life whose members mostly go undetected. I hope charting our stories about them (which are really stories about us) might illuminate the journey we’ve been on as ecosystemic beings.

In this essay, Pinto traces the metaphors through which we have understood both mushrooms and ourselves, from a catalogue of mushroom metaphors she gathered from articles published in 1985, the year she was born—“fungi as protectable resource, as teacher, as a way to commune with a different plane, as medicine, as object of study, as the ‘latest’ ingredient, as product, as monster”—to this list from 1997: “fungi as conduits for tree business, as proof against nature red in tooth and claw, as metaphor for connectivity.” Pinto’s journey through these metaphors gets at the way metaphors are inescapably political, from “[f]ungi as route to freedom, as queer, as cultural revolution” to “[f]ungi as world ender.” The essay is more an intuitive, informal taxonomy of these metaphors rather than an in depth exploration of any one of them, but it points in some interesting directions, both as a form—what other metaphors would be worth taxonomizing in this way?—and as the beginnings of a literary/poetic exploration of mushrooms themselves.

Four Things To See

All images are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and are in the public domain.

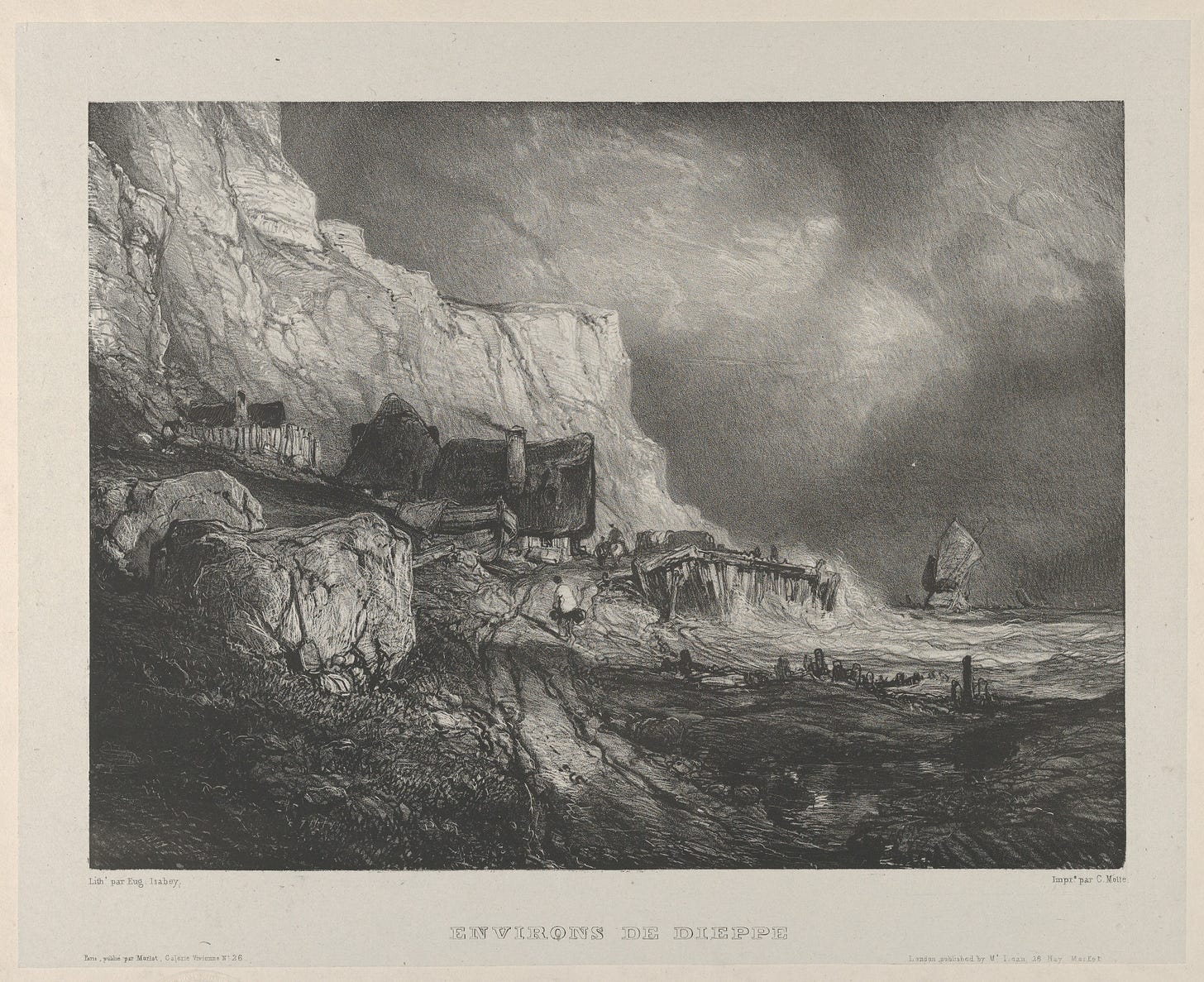

The Surroundings Of Dieppe (1833)

This print is part of a series of lithographs by Eugène Isabey printed by Charles Motte and published by McLean in a book entitled 'Six Marines dessinés sur Pierre' (Six Marinescapes drawn on stone) which featured studies of shipping and coast towns.

§§§

Fragment of a Leather Piece with an Erotic Scene (Egypt, The New Kingdom, ca. 1550-1458 BCE)

The erotic nature of the scene, with its naked male dancer, suggests that this piece was inteneded for the shrine of the goddess Hathor at Deir el-Bahri. In her aspect as a fertility goddess, Hathor was associated with Bes, a fertility god who was depicted as part human, part lion. The nude figure may be either a priest or a mummer who would have worn a mask and played the part of Bes at a festival honoring the goddess. The dancer and the partially preserved man in the register above both carry an object with multiple brown strands. These have been described as scourges, but they could as easily be some sort of percussion instrument used to accompany the music and to placate the goddess.

§§§

Kirkstall Abbey. Doorway on the North Side (1850)

§§§

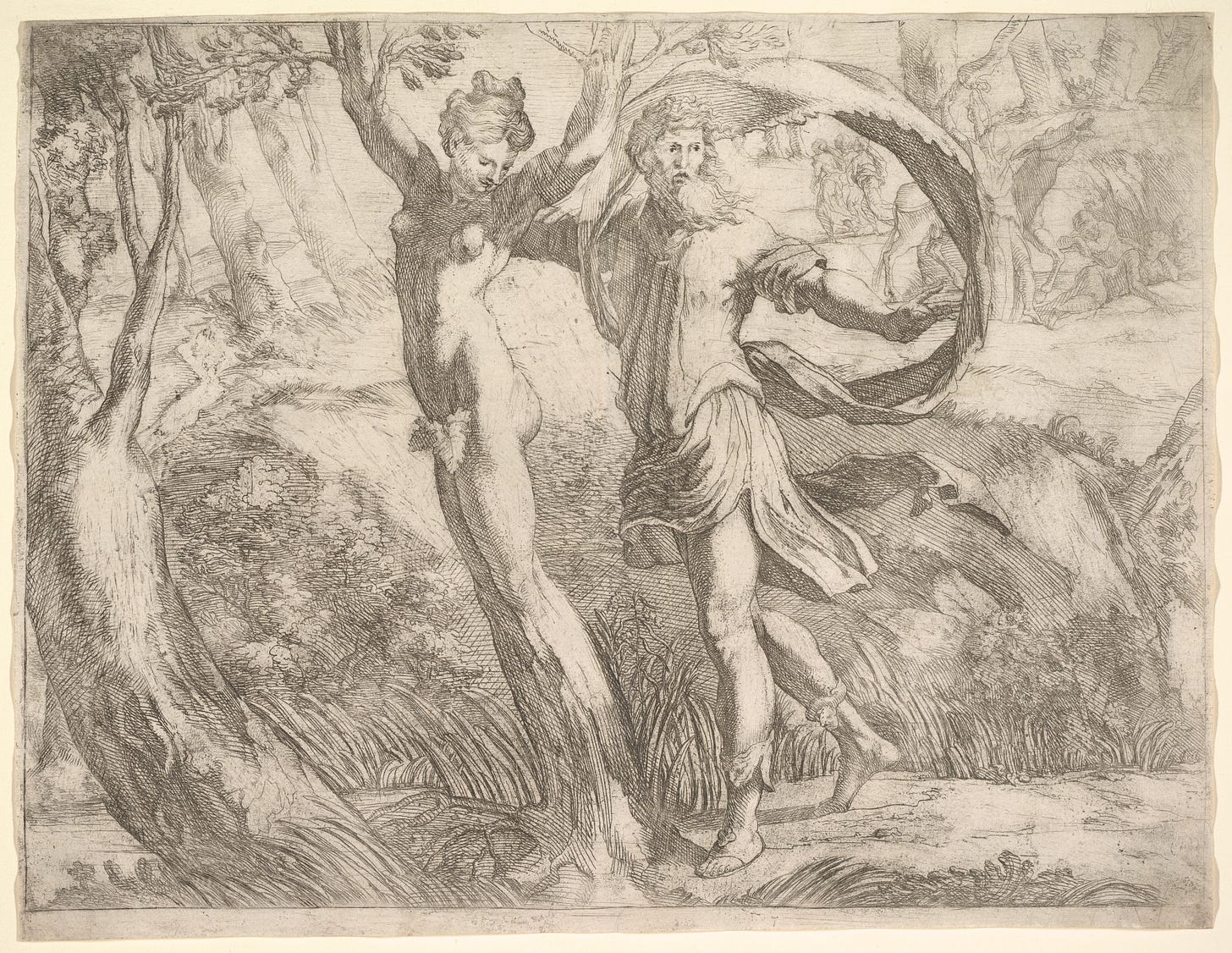

Priapus and Lotis (1530-1550)

the ithyphallic god of gardens and fertility and the incarnation of unbridled carnal lust, was a favorite character in the erotic poetry of antiquity and the Renaissance. Long believed to represent Apollo and Daphne, this print instead illustrates a scene from the story of Priapus and Lotis narrated in Ovid's Fasti (elegiac verses commemorating the rustic rituals and celebrations of the ancient Roman calendar) in which the fleeing nymph is transformed into a tree to avoid the rapacious god's advances. An act of censorship has removed, or, more accurately, obscured beneath an improbably swirling drapery, Priapus's enormous, offending phallus.

Four Things To Listen To

In these first two selections, I’m plugging two of my son’s bands: Minimal Absolution and Insurreal, both of them play death metal. My son is the bassist.

Minimal Absolution - Lifeless

§§§

Insurreal - Demonic GrinMinimal Absolution - Lifeless

§§§

Insurreal - Demonic Grin

§§§

Ofra Haza - Im Nin’alu

§§§

Tangerine Dream - Shadow Flyer

Four Things About Me

A small world story: Some years ago, I was buying something at the Apple Store near my campus. Seeing the faculty ID hanging from the lanyard around my neck, the sales rep who was helping me asked if I knew a certain professor from the Biology Department. I did, I said, and, because I always thought it was kind of a cool story to tell, went on to say that I’d gone to high school with his kids and that he had been the music director at the Jewish Center where I went to Hebrew School. The sales rep looked at me a little strangely and wondered aloud if I also knew his daughter, Adrienne. I did. She had been a classmate of mine and one of my closest friends. I even dedicated The Silence Of Men to her because she had, truly, “believed in my writing almost before I did.” Her father remembered me, of course. I’d been a guest at their house after Shabbat services more than once. “You were a rough kid,” he said, though he did not choose to elaborate, and I thought but did not say, “My god! If you thought I was rough, what would you call a truly rough kid?” (“Rough” was precisely the opposite of my reputation outside the yeshiva where Adrienne and I went to high school. I didn’t know until long after I was out of college that it had been what my classmates and teachers—and, clearly, some of my classmates’ parents—had thought of me.) I didn’t know if Adrienne’s father knew that she had essentially disavowed our friendship years earlier (after having not spoken for a decade at least, but that’s another story), so when he told me that his granddaughter was getting married, all I said was, “Tell Adrienne I said mazel tov.” Then I paid for my purchase and left the store. I did not see him again on any of my return trips.

§§§

I had a Catholic girlfriend in my twenties, a woman who had gone when she was younger, with her family, to a church where they still prayed—at Easter time, I think she said—for the conversion of the Jews. We were in love and had even begun to contemplate a future together. Once, we were laying in bed talking about something, I don’t remember what, when she said, “Why are you suddenly being so Jewish about this?” I was, as you can imagine, furious, and we fought, and I wondered, seriously, if this would mean the end of our relationship. What I remember most, though, is that when we talked after a couple of days apart—and I wish I could reconstruct more of the conversation than this—she said, “I am antisemitic,” by which she meant, she went on, not that she hated Jews (obviously), but that she’d internalized ideas about Jews that were antisemitic and that she did sometimes express them. “But I want to work on that,” she finished. It would be years before I fully understood what a remarkably high bar she’d set for the honesty and integrity that it takes to confront, especially in a relationship with someone you love, one’s own unexamined assumptions about groups of people who are Other to you, but I did learn from her how important it was to make the effort. We ended up staying together for five or six years after that.

§§§

I’m not going to tell here the full story of how that woman and I met, except to say that it was while we were working at a summer sleep away camp where, though the chemistry between us was palpable, we consciously chose not to pursue a romantic relationship of any sort. Instead, we became close enough as friends that, unlike the kind of summer camp connection that lays more or less dormant in the off season, we committed to keeping in touch, though the only way we could do so was on the phone or by letter, since we lived far enough away that visiting each other was almost completely out of the question. We fell in love, in other words, slowly, over a couple of years, in what could be described as a perfectly conventional Victorian courtship. I still remember the immense pleasure I took in both reading her letters and writing mine, especially the ones we took sometimes a week to compose, in journal-like entries that made it feel, or at least made me feel like we were in each other’s daily lives almost as if we were physically present. I realize this is probably generational, but the nearly instantaneous connection that digital communication makes possible—as moving and intimate as it can sometimes be—is just not pleasurable in the same way.

§§§

Fifteen or twenty years ago, I was recruited by a book packager, though we never actually signed a contract, to edit what was supposed to be an encyclopedia of marriage. The book never got published, at first because of my own inexperience as an editor and then, frankly, because I lost interest. (I also think the company may have gone out of business, though I don’t remember this clearly.) The one thing that did survive the death of that project was a part of the introduction I wrote, a brief essay that explored just how Victorian the letter-writing courtship I described above actually was. At some point, I realized that, with a few adjustments, I could turn that essay into a model of the kinds of research papers my students were required to write. Whenever I shared it with them, however, their initial response—aside from their interest in learning more about me and my early love life—was always something like this. “Wait,” and you have to imagine the tone of extreme disbelief in which these words were uttered, “you actually had to wait for a letter to arrive in the mail? That means everything she wrote about was already old news. What was the point?” They also could not imagine having the patience to wait for a reply. Then, inevitably, someone would say something like, “And you said you fell in love this way? How is that even possible?” Nothing I said in response satisfied them. We stood, very clearly, on opposite sides of a generational and technological divide.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion