Upcoming Events

It’s been a long time since I’ve given readings on a regular basis, but I am making a conscious effort to start doing so again. The second week of September is going to be a busy one!

- On September 9 at 7 PM, I will be reading at DADA in Ridgewood along with the artist and writer Lizzie Scheader. More information.

- On September 11 at 6 PM, I will be reading at Book Culture LIC along these fine writers: Aida Zilelian, Emily Hockaday, Jared Harél, Pichchenda Bao, and Stine An. Check out the Book Culture website for more their bios and other information.

- On September 13 at 2:30, I will be giving a talk/reading at the Jackson Heights Public Library called “How Writing Poetry Helped Me Come To Terms With What The Men Who Violated Me Did To Me.” More information.

Four Things To Read

A Poem (and a Painting) About the Suffering That Hides in Plain Sight, by Elisa Gabbert:

“But for him it was not an important failure” — this, I think, is the crux of [Auden’s “Musée Des Baux Arts] disaster’s in the eye of the beholder, and if the eye does not behold, it’s not disaster at all.

Gabbert does a deep dive into this poem, which is, nominally, a response to Breughel’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

A summary of the poem does not do it justice—it is about the significance of the fact that Icarus’s fall, which Auden uses to represent human suffering on a much larger scale, is a minor, insignificant part of the painting that you would easily miss if the title didn’t tell you to look for it in the lower right hand corner, the point being that the suffering of others is something we have to choose to pay attention to, that it is something we can look away from all too easily. Here are the first few lines:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

And here are the lines specifically referencing Breughel’s painting:

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure;

Gabbert’s digital tour through the poem is well worth paying close attention to. She makes the poem’s underlying mechanics visible and accessible and shows how Auden constructed them to arrive at the poem’s “meaning.” She also illuminates the poem’s ekphrastic nature by uncovering paintings it refers to in addition to the one Auden names. What struck me most, however, and made me want to include her article here is the way her analysis arrives at this:

“Musée des Beaux Arts”…offers no comforting slogans or rallying cries, no assurance that suffering comes to an end or happens for a reason…What the poem really does is ask questions. The truth, we might infer, cannot be told — the truth is always changing; the truth is an ongoing inquiry…It asks us to question our place in the world — to ask what we might be missing…Do we spare a thought for…suffering, or sail calmly on? Moral absolution is available, the poem seems to say. That doesn’t mean we deserve it.

We often ask what good poems can do in the face of the suffering inflicted by, for example, Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza, or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or the famine in Sudan—not to mention the Trump administration’s attacks on migrants, women, and people who are trans and queer. (That list could, obviously, go on.) Gabbert’s piece, it seems to me, embodies one answer to that question. Poems, good poems—in both the aesthetic and moral/ethical senses of good—offer us emotional and intellectual access to the complex interiority of what it means that we have a choice whether or not to bear witness to suffering, much less to take whatever action we can to end it. Gabbert’s essay is worth reading and talking about and I think it is especially worth teaching.

§§§

Ghosts of the Groves, by Gavriel Cutipa-Zorn:

In May 2019, shortly after he became governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis traveled to Israel and the West Bank, accompanied by more than 100 of his state’s legislators, lobbyists, and businesspeople. He sat down one-on-one with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (after which he boasted that Florida is “the most pro-Israel state”); became the first Florida governor to visit a West Bank settlement (where he received an honorary degree from Ariel University, the only accredited Israeli university located in the settlements); and held a state cabinet meeting at the US embassy in Jerusalem—a violation of Florida’s Sunshine Law, which specifies that state meetings must be accessible to the public—during which he signed a bill adopting the controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism, making criticism of Israel punishable in Florida’s public schools and universities. His office celebrated the trip as a “historic business development mission,” touting the potential to forge new commercial ties between Israel and Florida.

This article, from Jewish Currents’ Summer 2024/Florida issue traces both the parallels between the orange industries here and in Israel—exploitive, extractive—and the socioeconomic and political connections between them, which DeSantis’ visit epitomized. For me, having been raised watching Anita Bryant say on TV, “A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine,” this was a real eye-opener. Not because I think it is possible for any industry to be fully innocent of exploitive/extractive practices, but because orange juice is one of those things I have so taken for granted as part of my life (a result of the industry’s marketing practices, of course) that not only has the story behind it been invisible to me, but it also never occurred to me to be curious about that story.

§§§

“In the Middle of Fighting for Freedom We Found Ourselves Free,” introduced by Alexis Pauline Gumbs:

The loving sisterhood between [June Jordan and Audre Lorde], forged during the Civil Rights and Black Power struggles in New York City, had broken down amidst divisions in the feminist movement about how to show up in solidarity with the people of Palestine and Lebanon following Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon. (Jordan sharply called out feminists who identified as Zionists, while Lorde tended to build bridges with Jewish feminists who critiqued but did not entirely divest from the State of Israel.)

This quote, from Gumbs’ introduction to June Jordan’s remembrance of Lorde the year after Lorde died, articulates a tension I have run into in my own discussions with people about what is happening now in Palestine, and I was surprised to learn that it had caused a rift such that, as far as Gumbs has been able to find out, the two women stopped speaking to each other some time in the 1980s. Jordan’s remembrance is worth reading because it embodies what it means to resolve—even though in this case she was too late—the sometimes fundamental differences in how those of us on the same side choose to fight “against hatred and [for] the annihilation of all bigotry.”

§§§

Why Are Men So Obsessed With Pornography?, by Robert Jensen:

Pornography has become more intensely cruel and degrading to women. Pornography is without question the most openly racist mass media genre. Scenes of rough sex that pornographers once considered too dangerous to market are now considered unremarkable. Girls report that the boys they date want to replicate those scenes during sex, including strangulation. Young women report abandoning the hope of a male partner who doesn’t use pornography. Women in relationships with men report a sense of betrayal when partners refuse to give up pornographic pleasures. And then there are the women used in the production of pornography, the women Andrea [Dworkin] demanded that we never forget. I don’t mean the “porn stars” who explain how they are empowered by the pornography industry. I’m not mocking those women but simply pointing out that they are not representative of an industry that, as one pornography producer told me, “chews up and spits out women.”

I have always found what used to be called the “porn wars” profoundly frustrating because the polarizing stances that each side took seemed to me, more often than not, to be an excuse not to listen to each other, as if each side were proactively trying to shut down any possibility of substantive and productive discussion. Jensen’s anti-pornography take is among the more reasonable that I’ve read in that he does seem genuinely to listen, or at least want to listen to and understand the other side. Implicit in his argument, though I think you have to dig kind of deep to find it, is the idea that the problem with pornography is not the existence of sexually explicit imagery per se, but rather with an industry that produces such images in the service of a patriarchal view of women as subhuman sexual objects that exist solely for the pleasure of men. I am going to leave aside here all the ways in which that characterization can be critiqued and debated—including the question of whether it is possible in today’s society to make an ethical pornography—to focus on what I think is valuable, what I have always thought is valuable, about the radical feminist anti-pornography stance: the way it strips away, if you take it seriously, the layers of denial men require not to see that protecting the industry I described above means by definition that we are choosing the pleasures we derive from its product over the well-being of women. Disagree all you want with the anti-porn stance as a whole, but this aspect of it is one that men especially should wrestle with, and it is what makes Jensen’s essay worth reading. (As an aside I will add that the book review I linked to above made me want to read the book under review, The Pornography Wars, by Kelsey Burke.)

Four Things To See

All images are from the Library of Congress’ William P. Gottlieb Collection, which consists of jazz photographs taken by the writer-photographer from 1938 to 1948, the “Golden Age of Jazz.”

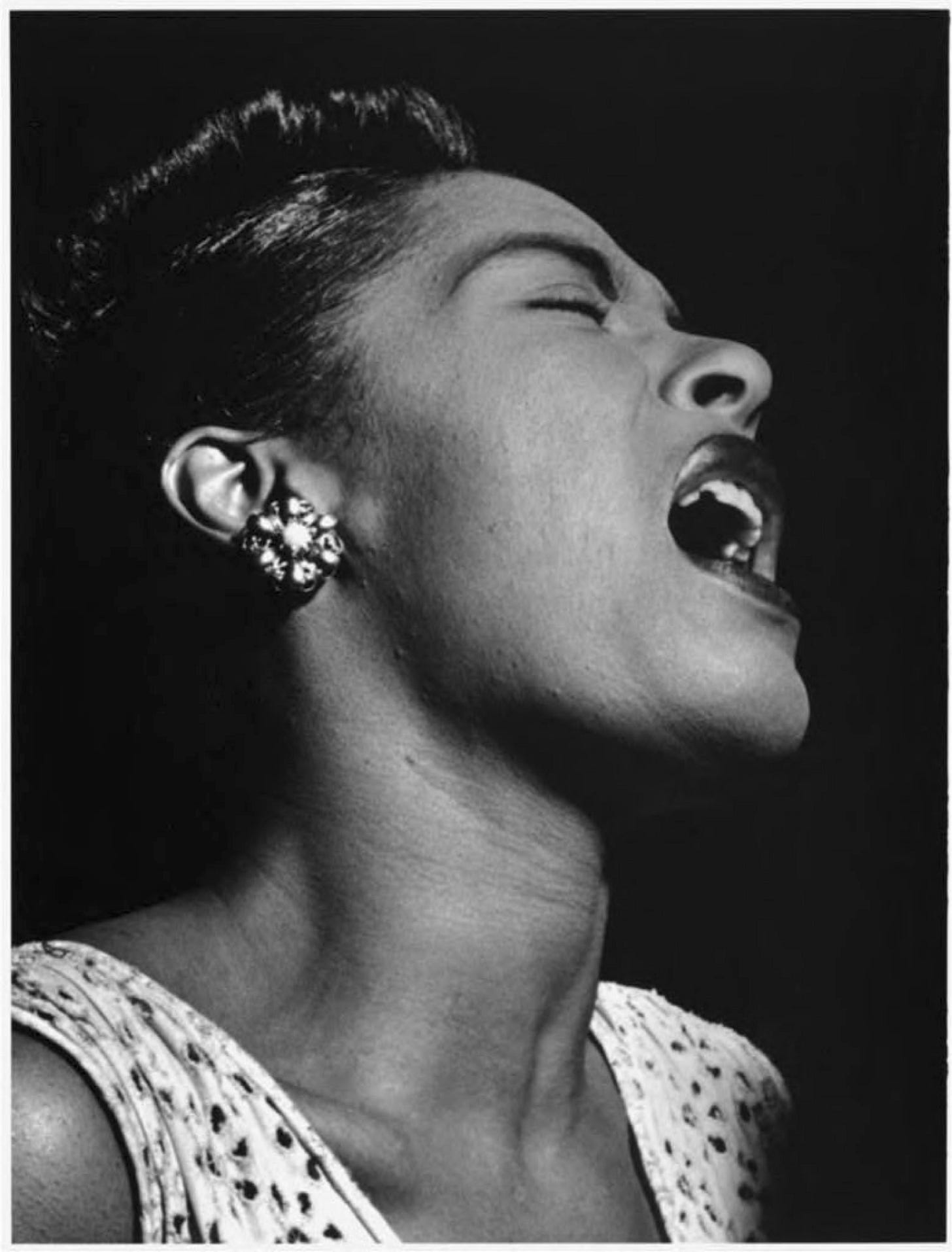

Billie Holiday

Published in Downbeat, New York City circa. Feb. 1947

§§§

Ethel Waters

This portrait was taken sometime between 1938 and 1948, perhaps in New York City

§§§

Mary Lou Williams

Taken in New York City, circa 1946

§§§

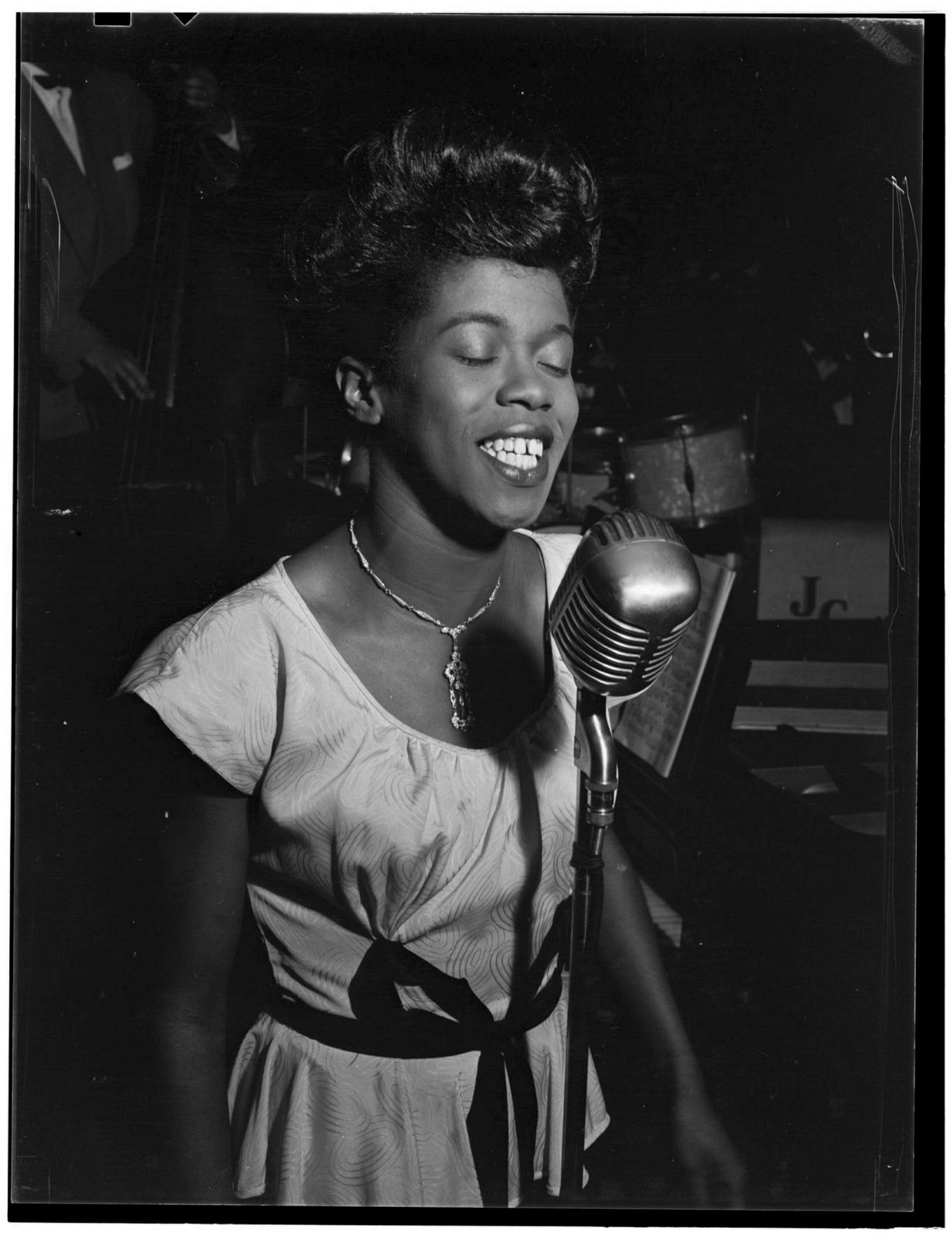

Sarah Vaughn

Taken at Café Society (Downtown), New York City, circa Aug. 1946

Four Things To Listen To

Adam Ben Ezra - Downtown Blues

§§§

Kamalata - Dirty

§§§

Renee Rosnes Trio - I Hear Rhapsody

§§§

War Poem

Video by Taira Akbar, Words by Ralph Nazareth and Robert Roth, Music by Hendrik van Oordt

Four Things About Me

My mother cured me very early on of any desire to smoke cigarettes. I don’t recall exactly how old I was, but I was not yet a teenager because she was still married to George, her second husband. We were sitting outside the building where we lived, me, her, George, and my younger brother Paul. She and George were smoking non-filter Camels, their brand of choice. I don’t know why, but my mother suddenly asked Paul if he wanted to try. When he said yes, she handed him her cigarette and he started smoking it with ease. Clearly, he’d done it before. She turned to me and asked if I too wanted to try. I don’t think I wanted to smoke per se, but I wasn’t about to be outdone by my little brother. So I took the cigarette she handed me, the same one my brother had been puffing on, and inhaled a full breath of smoke deep down into my lungs. I thought I was going to be sick! I have not smoked a cigarette since.

§§§

The unpleasantness of that experience was one reason I waited as long as I did to try marijuana. I could not imagine that getting high, whatever it felt like, was worth burning my lungs from the inside out. The other reason I did not try pot until I was seventeen—which, among my peer group, was really late—was that I wanted to do it on my own terms, not to satisfy my friends’ desire to “see what Newman’s like when he’s stoned.” When my curiosity finally got the better of me, I told my best friend Joey. We waited till I knew my mother was not going to be home and sat in my room while Joey rolled the joint we were going to smoke. He showed me how to hold it between my fingers and how to “take a toke,” while also emphasizing the importance of not treating the joint like a cigarette. Then, making sure the window was open, he lit it up and we smoked it. I felt nothing, which Joey told me was not unusual, so I tried again after a few days had passed and I did indeed get high. I don’t remember especially liking or disliking the feeling, but I did, on occasion, join in with my friends when they “partied,” which was the term they used because the word smoking was reserved exclusively for cigarettes.

§§§

Joey joined the army when we were sixteen. I have a distinct memory of sitting with him on the wooden fence outside his building late one night after he’d snuck out of his room and him telling me that he had to get out of there because his father was an asshole. I liked his father, or at least I thought I did. He ran the drum and bugle corp Joey and I both marched in, and he was funny. He knew how to tease boys in a way that made them feel seen and included, which was something I very much needed at the time, especially after George left us. So it was hard for me to imagine the man as the asshole Joey said he was. Now, though—and I have thought this for quite a long time—I’m not so sure. Working backwards from the fact that Joey killed himself in his early twenties, after at least two unsuccessful attempts that I heard about, and coupling that with the completely intuitive but nonetheless deeply skeevy feeling I get now when I remember his father—where that feeling comes from is for another time—I wonder if Joey wasn’t trying to say something a good deal more disturbing than that his father was an asshole. As far as I know, no one tried to reach out to me about coming to the funeral, and when I got home at the end of the summer, no one talked about Joey—no one wanted to talk about him—at least not to me, not even his younger brother, with whom I’d also been friends. I think there was a lot more shame surrounding suicide back then than there is now, which may have been the reason for everyone’s silence, but it was as if my friend had simply vanished without a trace. Shortly after that, I learned that his parents got divorced. It may simply have been the stress of dealing with their son’s suicide; it may have been tensions in their marriage that were there all along; but I also can’t help but wonder what Joey’s mother might have learned about her husband to cause her to want to leave him.

§§§

The night before Joey left for the army, he and some of our “rougher” friends managed to buy a couple of six packs of beer they planned to drink by the railroad tracks behind the development where we lived. The cops caught them, however, and confiscated the beers. I can’t recall exactly how it happened that one of those cops—I think we always called him Sargeant Marino—told me he would give the beers back to me, but I have a distinct memory of him telling me he knew it was Joey's last night at home and that, as long as we didn’t make any trouble, he’d return the beers to me. Why me? I assume because I was known as the mature one among my peers. Maybe Sargeant Marino figured if I delivered the message, my friends would keep up their end of the bargain and drink Joey’s farewell in peace. I have a vague recollection of Marino taking the six packs out of the trunk of his cop car and of me bringing them to where Joey and the rest were sitting near the front entrance of the neighborhood elementary school, but after that my memory goes blank. One thing I know for sure, though, I did not drink that night, for much the same reason that I didn’t smoke cigarettes. I couldn’t have been much older than five or six, sitting on my father’s lap in his parents’ kitchen and listening to him and his father talk about the horses—they both loved to bet on the races—when one of them, I don’t know which, though I think it was my grandfather, asked me if I wanted to taste the beer the two of them were drinking. I said yes, of course, but regretted it the moment the liquid hit my tongue. I don’t think his intent was, as I assume my mother’s was with the cigarette she gave, to put me off drinking, but that was the result. I did eventually come to like the occasional beer—I rarely have more than one; and I will almost always choose some other kind of alcohol if I have a choice—but that was not until my twenties.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion