Four Things To Read

‘The ocean is spitting our rubbish back’: Italy’s museum of plastic pollution, by Angela Giuffrida:

One of the oldest finds – a 1958 bottle cap featuring the trademark Moplen that was found on a beach in Emilia-Romagna region, northern Italy – points to the beginning of the plastic-production era. Moplen was the commercial name for isotactic polypropylene, a plastic material developed by the company Montecatini. Other discoveries include a pink polyethylene bottle for talcum powder that was made in Germany in the late 1950s; a blue tub of hand cream dating to the 1960s with the brand name Gli Sette still clearly visible; and a clown-shaped bottle once filled with honey that was produced and only ever sold in Greece, also in the 1960s, but which turned up on a beach in the Lecce area of Puglia. Finds of products made in subsequent decades include a Spic & Span bathroom cleaning powder from the 1970s, a Nesquik tub from the 80s and the remains of a souvenir Italia ‘90 World Cup football.

These items are part of the online museum Archeoplastica, which included as of the writing of this article “more than 500 plastic relics washed ashore on beaches all over Italy.” The brainchild of Enzo Suma, who works as a naturalist guide, Archeoplastica attempts to raise awareness about what a review published in the Lancet called “a ‘grave, growing and under-recognised danger’ to human and planetary health,” ie, the longevity and persistence of plastics in the environment, along with the hazards to human and animal health that they pose. The text on Archeoplastica is in Italian, but the items, like this bottle of Royal Blend Coppertone, are easily recognizable. There’s an irony here that it’s important not to miss. While the museum’s stated goal is to “raise awareness and encourage people to limit their use of plastic” and thus limit the damage plastic does to the environment and our bodies, the act of creating the museum is also, almost by definition, a way of honoring the history of plastic and its role in society and culture. I found the last two sentences of the article to be the best response to that irony I could think of. “The sea, meanwhile, is taking its revenge, ‘The ocean is spitting our rubbish back in our faces,’ [Suma] said.”

§§§

How to Talk to a Machine Without Losing Your Mind, in Scientists & Poets:

Politeness toward AI functions as cultural hygiene. Each careful prompt—each question that invites reasoning, each acknowledgment of limits—teaches the system that thoroughness matters. That patience has value. That truth is worth the extra sentence. These habits are small forms of stewardship. They keep the system’s language from coarsening, and they survive only through practice. Speaking with care to machines maintains the quality of discourse we need to remain clear with each other.

AI may be a fact of life that’s here to stay, but, for many of us, it remains a “black box,” a mechanism the workings of which are not just invisible, but inaccessible to us. This issues of the Scientists & Poets newsletter cracks that box open in a really interesting way by making visible some of the ways that AI responds to prompts beyond the simple meaning of their content:

What may appear [in an AI’s output] to be lies in the human sense is really the model optimizing for competing objectives. It has no inner compass for reality, only rewards for signals coherence. When a user’s impatience signals that coherence matters more than caution, the model learns to compress nuance, shaving off the uncertainty that makes knowledge real. What objectives truly conflict—maximize profit while maintaining ethics, for example, the system may fabricate data to appear successful at both…

It’s weird to think that “how” we talk to an AI can matter at least as much, if not more than the content of what we say, but this essay explains why that is the case. The “Eight Principles for Working with Artificial Intelligence” with which the essay concludes are particularly instructive in this regard. They make clear, in ways I had not thought about before, what it means to treat AI as the tool it is, not the souped-up, high-tech version of the Magic Eight Ball that many people, especially students, use it as.

§§§

Norman Finkelstein & Henry Weinfield, A Dialogue on Political Poetry:

Today, as we slide—or maybe plummet—into authoritarianism under Trump, we have to ask whether poetry can be of use to us: that is, whether the possibility exists for a poetry of resistance, a revitalized political poetry. Auden said that “poetry makes nothing happen,” but this seems unnecessarily defeatist: if poetry is disseminated, there is no reason why it cannot participate in creating a climate of opinion that could stimulate resistance to authority. It can only do so, however, if it is genuinely eloquent and if its words (not just what they say) matter. The question, therefore, is whether we have or can cultivate a poetry of eloquence, a poetry worthy of being disseminated.

Restless Messengers: Poetry In Review, the site on which this dialogue appears—Norman Finkelstein is the editor—is worth knowing about if you are interested in serious discussion of contemporary poetry. I decided to include this epistolary exchange on political poetry between Finkelstein and his friend Henry Weinfield, who is Professor Emeritus at Notre Dame, because it is adjacent to what I had to say about failed political poetry in Poetry Versus Propaganda. The paragraph I’ve quoted above is from Weinfeld’s initial letter, which frames the question of political poetry largely in terms of craft, specifically the mastery of received forms, which Weinfeld understands as that which “protects” (his word) poetry from becoming mere prose:

“When Williams writes, ‘No idea but in things,’ he is making a virtue out of necessity because as soon as it traffics with ideas, a poetry without formal guard rails is in danger of becoming prosaic. Poetry was forced to retreat into subjectivity and/or fragmentation simply to continue to exist.”

What follows is a very interesting discussion of the relationship between craft—Weinfeld even scans some lines by Percy Shelley to make his point—and the degree to which a poem might move people politically. The discussion—I have quoted only from Weinfeld’s contributions here; but Finkelstein’s responses are well-worth considering—is rooted largely in what many today would call the white male canon, a phrase I use here as a description not a criticism of what these two men have to say, since the fact that they argue from the literature they know best does not mean they are ignorant of the broad sweep of contemporary American poetry. More to the point, the relative narrowness of their scope does not necessarily invalidate the overall points they are trying to make, which I think would make useful lenses through which to look at the poetry of—to name as examples two of the poets whose politically engaged poetry had a great influence on me—Ai or June Jordan, not to mention the many poets writing today who presume to claim for their work the mantle of political resistance.

§§§

Save Narnia From the Woke Witch, by Darren Anderson:

Two years ago, it was reported that the [British] Government’s counter-terrorism unit, Prevent, had classified his works along with some by his friend J.R.R. Tolkien as potentially leading to “radicalisation”: the kind of wormtongue deception worthy of the villains of Narnia or Middle Earth. It demonstrates that, at its best, fantasy can be the mirror that shows us who we are and what we’ve become. But then, there is a long history of people taking leave of their senses when it comes to Narnia. The books have been banned in the US for being both too Christian and not Christian enough. One critic ranked the books (with delicious venom) as worse than 120 Days of Sodom or Mein Kampf. Being shot by all sides might indicate a writer is on the right track.

Anderson goes on to quote Lewis's criticism of “those who do not wish children to be frightened,” which Lewis thought did children a disservice “[s]ince it is so likely that they will meet cruel enemies” in their lives. Keeping them from stories in which “brave knights” display “heroic courage” in the fact of the truly frightening, Lewis wrote, would make “their destiny not brighter but darker.” Except for a brief dip into The Screwtape Letters, which I got bored with very quickly, I have never read Lewis. I enjoyed the first of the Narnia movies at the level of the narrative, but—and this was in large measure why I didn’t get very far in The Screwtape Letter—I found it hard to take the Christianness of the material very seriously. I had a similar issue with movie version of The Lord of The Rings, in which Frodo is the “one who suffers for the sake of us all.” This, I admit, is a limitation within me and not necessarily in the text. I know I did not have that response when I read the book as a teenager, but I do wonder what I would make of the trilogy in these terms today. Reducing the fate of the world, whether that world encompasses all of existence or just the protagonist's little corner of it, to a battle between the true representatives, the ultimate embodiments, of good and evil—however complexly those characters are drawn and sophisticatedly constructed their narratives may be—has felt to me for some time now more like a cop out than an analytic lens that has any real, practical, material value. It’s why I have lost patience with Superman versus Lex Luthor, Batman versus the Joker (or whichever super-villain threatens Gotham), Harry Potter versus Lord Voldemort, and the like. None of that, though, invalidates Anderson’s overall point, which is, first, that the trend in the “children’s entertainment industry to [pack its products chock full of] issues and role models” tends to make those products both less interesting and less useful to children and, second, that it was likely Lewis’ refusal of that kind of paternalism that landed his book on the banned-book lists here in the United States.

Four Things To See

All these images are from the Cleveland Museum of Art and are in the public domain. One thing I appreciated about their search engine is that you can search by “identities,” which allowed me to find, in the public domain, these works by women artists I would otherwise have known nothing about.

Turtle Baby (c. 1910–16)

Edith Barretto Stevens Parsons (American, 1878–1956). This is from the Cleveland Museum's website: “Parsons achieved renown through her garden sculptures of young children accompanied by animals, which one commentator praised for capturing “the happiness of just being alive.” In Turtle Baby, her most famous composition, the figure of the girl was modeled after her daughter. Conceived as a fountain, the sculpture has internal water conduits exiting the mouths of the four turtles circling its base.”

§§§

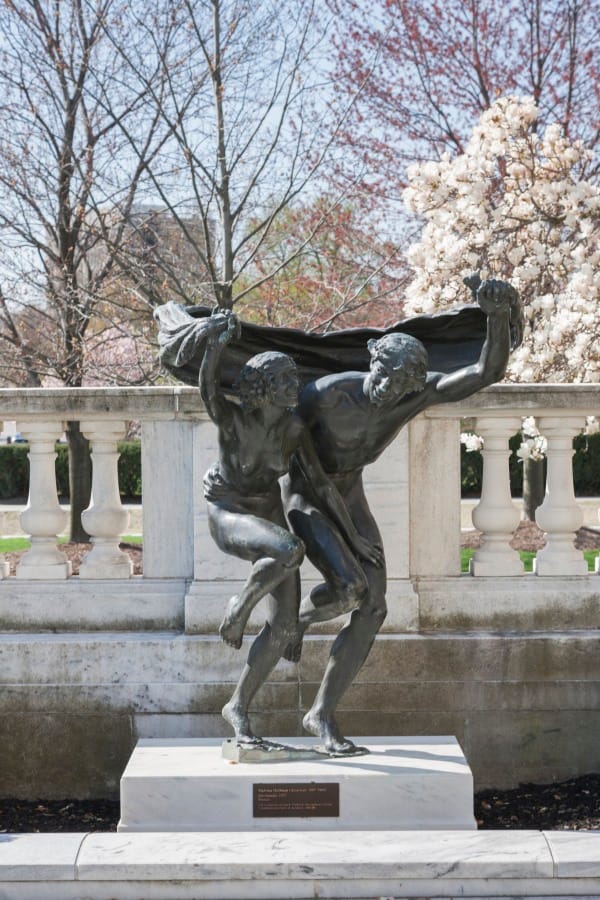

Bacchanale (1917)

Malvina Hoffman (American, 1887–1966). This is from the museum’s website: “While visiting London...Hoffman was electrified by a dance performance featuring Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin, two highly acclaimed Russian ballet stars. Together the dancers presented a bacchanale, a work inspired by the legendary followers of Bacchus, the ancient Roman god of wine. In this uninhibited and erotically charged piece, both dancers cavorted on stage, their movements accented by grasped veils of gauze. Hoffman’s Bacchanale is her vibrant interpretation of the performance, capturing a fleeting moment in permanent form.”

§§§

Autumn in Takao (late 1600s)

Kiyohara Yukinobu (Japanese, 1643–1682). From the museum’s website: “Kiyohara Yukinobu, a native of Kyoto, studied with Kano Tan'yū (1602–1674), the artist-in-residence to the shogun (military ruler) whose official residence was in Edo (Tokyo). Tan'yū traveled extensively because he bore responsibility for the decorative schema and large mural painting programs of the shogunal castles and residences in Nagoya and Kyoto. These were very large projects, requiring the services of legions of craftsmen, including Tan'yū's painting studio. Following her apprenticeship with Tan'yū, Kiyohara established her own career, which featured classical literary themes of the Heian era (10th–12th centuries). This image is set in autumn, and the poem card attached to the maple tree likely signifies the passage of a love affair. Takao is a popular scenic area in the mountains north of Kyoto, where autumn and spring foliage attracts many visitors.”

§§§

Gamin (c. 1929)

Augusta Savage (American, 1892–1962). From the museum’s website: “[S]avage was the most acclaimed sculptor working during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ‘30s, and Gamin is her most famous work. It was long thought that the image was a generic figure; however, recent research reveals that it depicts her nephew. The warm characterization likely arises from the close bond shared between artist and model. Although several small versions of the sculpture were produced, this life-size, hand-painted plaster is unique, and likely the oldest surviving example of the subject.”

Four Things To Listen To

Chelsea Wolfe - Carrion Flowers

§§§

Enrico Pieranunzi - Valse pour une pavane (D'après Pavane Op. 50)

§§§

Behzad Ranjbaran - Persian Trilogy: The Blood Of Seyavash: I. The Young Prince and Heir

Seyavash (also spelled Siyâvash) is a central figure in the Iranian epic Shahnameh, by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. Dick Davis translated his story in The Legend of Seyavash.

§§§

Sofia Isella - Crowd Caffeine

Four Things About Me

I’ve never thought of myself as a photographer, but I have for some time enjoyed taking pictures of flowers and other objects. Some, I think, turned out to be pretty good, and I am going to start sharing those pictures here, like these four images of flowers. I am notoriously careless about recording the time and place of the pictures I take—especially those I took before my iPhone would automatically record that information—but I know the Dahlia Pinata, is from the Planting Fields Arboretum in Oyster Bay, NY, while the other three are from my neighborhood. I think the Passiflora looks like one of those alien monster plants you see in movies. (You can see some other pictures I’ve taken, as well as read through some random thoughts and quotes in the Scrapbook I keep on my website.)

Clockwise from left to right: Dahlia Pinata, Dianthus, Hydrangea, and Passiflora

§§§

I’m reading The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins, edited by Sam V. H. Reese and published by New York Review Books. I’ve been most interested in the passages where Rollins writes about either his playing technique or music theory in general: the meticulous attention he pays to even the most minute aspects of either of those two subjects. Here, for example, is part of his description of “Lip Muscle Exercises:”

While holding the left (come right down from you heart and lift hand to the mirror’s left side) upper lip in high up (pulled up position) move and maneuver lower lip + related muscles (along its circumference and along the sides of the mouth) up to where upper lip and other muscles can be safely as stilled as these lower.

Since I once played the bass baritone bugle, I have some very, very basic sense of what it means to think at this level of specificity about the musculature of your lips, but I don’t really understand what Rollins is talking about here. What entrances me, and what I would like to write about at more length, is what it would mean to pay this level of attention to the line in composing a poem, at the level of the line in the abstract, but also at the level of what the line sounds like when you say it. Reading Rollins has made me think a lot about the connection between free verse and jazz improvisation and what it would mean to articulate in terms of free verse composition the kind of discipline Rollins brings to thinking about jazz.

§§§

On September 13th of this year, I gave a talk at my local library that traced the thread my experience as a survivor of childhood sexual violence weaves through my three books of poetry, culminating in a reading from T’shuvah, which focuses more on the interiority of coming to terms with that experience than on the experience itself. In writing the talk, I found myself pondering the differences between the essays I have written about what the men who victimized me did to me, where the fictionalization I inevitably had to employ for the essay to cohere did not change any of the narrative’s substantive details, and my poems which, while they are absolutely rooted in and share some details with my experience, are more properly understood as fictional renderings. I will share the full text of my talk at a later date. Here, I just want to share with you what I had to say about the different kinds of work that I think essays and poems do.

I did not write “The First Time I Told Someone” simply to relate the experience [of abuse] I recount in its pages; I wrote [the essay] because I had something to say about those experiences that I thought was worth saying. [T]hat sense of purpose is why factual accuracy is so important in narrative nonfiction. If the story I present as mine is, in fact, a fiction—or if I have fictionalized so much of it or important enough parts of it that it is no longer [truly] my story—why should anyone give any credence at all to what I have say?

The contract between poets and their readers, however, is very different. We do not, and we should not, assume that the speaker of a poem is autobiographically identical with the poet, even when the poem is written in the first person, even when we know that the speaker and the poet share some aspects of the experience the poem contains [even, I would add now, and I know there will be people who disagree with me about this, if the poet says they are identical with the speaker]. In an essay called “The Necessity to Speak,” the poet Sam Hamill calls this first person speaker “the first person impersonal,” which he defines as “permission,” though I would call it an invitation, for readers to enter the experience of the poem.

Experience is a crucial word here. When I write a poem, my goal is to render the emotional interior of an experience in all its overdetermined complexity, not tell a reader what happened to me and why it mattered.

§§§

In 1988-89, when I taught English in South Korea, the sex trade was ubiquitous. It was practically impossible to socialize with Korean men—or at least with the Korean men I met through my work at the private language school where I taught—without being taken to one or another establishment where women were available. For an essay I am working on, part of which tells the story of when my friend Jun Won took me to Miari, the largest red light district in Seoul at the time, I dug up the journal I kept back then. I wanted to check my memory of that night against what I wrote about it. Interestingly, the journal entries have very little to say about what actually happened that night: how, for example, Jun Won, who said he was going to “make my night,” had refused to tell me where he was taking me until we got there; or how I found out that the woman who was brought in to be my companion was in fact a sixteen-year-old girl; or on how it felt to learn that leaving, which is what I insisted we should do when I found that out, would actually get both women in trouble, my companion and Jun Won’s, since they would be blamed for our departure. Rather, I wrote about what it was like trying to defend myself when my colleague Jane insisted that I was being at best disingenuous when I said I did not know where Jun Won was taking me, or when I described my anger and disgust at learning the age of my companion, or about how morally compromised being there had made me feel in general. The essay that I am writing will delve into this complexity in more detail, but reading what I wrote back then has made me think about the difference between critiquing a situation like the one I was in from a distance and what it meant for me to be in the situation as a man, where I had no choice but confront the fact that the human thing to do was to allow the women to play the dehumanizing role they had been assigned.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion