Four Things To Read

They Killed My Source, by Shane Harris:

A “huge number” of Iranian cyber operations “had my signature on the paperwork or I designed it altogether,” Mohammad claimed. At the time, Iran had been credibly linked to disruptions of the global financial system and to the penetration of computers that run crucial infrastructure, such as electrical grids and dams, including one in New York State. Was I now talking to the guy who oversaw those covert operations? And if so, why was he talking to me?

This piece in the Atlantic reads like the intricate subplot of a spy movie. According to Harris, he was contacted by a man named Mohammad Hossein Tajik, who claimed both to be in charge of an elite cyber-warfare unit in Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security and to have been a CIA asset within Iran. Both claims, Harris discovers, were true. Neither that fact alone, however, nor the far more chilling fact that Mohammed is eventually killed, almost certainly by Iran’s government, are what make this essay worth reading, especially now, given the ongoing unrest in that country. What I found most compelling about the story is the way it locates the geopolitical conflict between the US and Iran within the lives of ordinary human beings and demonstrates, by implication at least, how distant that conflict is, despite the players’ ordinariness, from the real, material, and ordinary interests of the ordinary Iranians who are now taking to the streets.

§§§

Salient, by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr:

My situation is difficult: I have to reconcile the trig and leveling data of the various systems available for this area…with my own emotions—complex mathematical calculations and a feeling of loss.

Salient is a book-length poem in which Gray explores what emerges when she brings into juxtaposition what she calls in her Preface “two obsessions of mine,” the Battle of Passchendaele, which took place in late 1917, and the chöd ritual, which she describes as “the core ‘severance’ practice of a lineage founded by Machikn Lapdrön, the great twelfth-century female Tibetan Buddhist saint.” That description might make it sound like you need either specialized knowledge of or a pre-existing interest in either subject in order to appreciate the book, and I am sure that people with that knowledge or that interest will be able to read Salient at a much deeper level than I did. Nonetheless, I found the poem to be a compelling and moving meditation on meaning-making. The excerpt I quoted above, for example, from “In Some Ways The Situation Is Analogous To That Facing Second Army in 1915,” can also be read as an account of the difficulties a poet encounters in trying to reconcile the mechanics of craft with the the emotional impulse that pushes a poem into existence; and the beginning of “General Description Of The Line,” which is, on the surface about military strategy, can also be read as a way of thinking about poetic composition:

The first line generally consists of two parts, one an obstacle,

and is continuous except for narrow inconspicuous passages

that may serve as exits.

Interestingly, a question the book asks without asking or definitively answering it is this: If making war requires the same kinds of imaginative engagement with reality as the making of art, then the imagination is truly amoral. What, then, are the constraints we can put on the imagination that will harness it to a moral purpose?

§§§

Is It Possible to Atone for Genocide?, by Avigayil Halpern:

As we approach Yom Kippur, I am left wondering: What does repentance look like as we try to move forward, both as a Jewish community, and also as part of the human community? How do we understand our own complicity and the specific ways we each need to be held accountable? For those of us who have opposed the genocide since its beginning: How do we relate to people who had been more reticent to speak out against Israel but are doing so now? We know that for hundreds of thousands of people, this reckoning is far too little, far too late. And still, this is not an intellectual exercise. For me, this question matters insofar as it can help hasten an end to the genocide, which needs to be our primary focus right now.

Before telling you whose words those were, it’s important to say that the conversation of which they were a part first appeared in Jewish Currents in the October 2025 “Chevruta,” the column the magazine models after “the traditional Jewish method of study in which a pair of students analyze a religious text together.” I deeply appreciate that the magazine honors in this way a thread in Jewish culture that often gets subsumed beneath the homogenizing press of the culture at large, i.e., that in the Jewish tradition individuals are responsible for coming to their own understanding of what it means to live a Jewish life by “learning Torah,” engaging on a personal level with the texts of the tradition. It doesn’t mean that we are our own absolute authority, but that we are responsible for making sense of the tradition on our own terms within the ever-widening context that the tradition makes possible as it evolves.

So, the words I quoted above belonged to Audrey Sasson, the executive director of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ) with whom Halpern was in conversation. Interestingly, Sasson does not ask about what teshuvah, the Hebrew word for atonement, would look like for, say, Netanyahu or other members of the Israeli government, or even for the Israeli soldiers who fought in Gaza. Rather, she is asking about those Jews here in the United States, and specifically for the Jewish leadership here in the States, whose move from complicity to opposition raises the question of why the move itself came so late in the game. The answers that she and Halpern come to—based on their readings of Maimonides, the Mishnah tractate Horayot, and On Repentance and Repair, by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg—are worth dwelling on. For the sake of brevity, though, I will just name a couple: the idea that the confessional component of atonement needs to come at the end of an internal process, not at the beginning of that process; the idea that someone who repents a murder they have committed should never be allowed to return to a position of authority they formerly held; and the differences between and among individual, collective, and institutional accountability.

On a personal level, this conversation reminded me of a question I did not have the courage to ask about teshuvah when I was in yeshiva: Would teshuvah have been possible for Hitler? The point of asking that, for me, was not to try to enumerate what such repentance might look like—the answer to that is far beyond my capabilities—but rather to test a related question: If repentance is not available to everyone, regardless of the wrong they have done, then is there really such a thing as repentance to begin with?

Emerson in Iran: The American Appropriation of Persian Poetry, by Roger Sedarat:

As important as source language remains in any discussion of literary translation, Emerson further follows the Sufi mystics in his conception of an ideal poet who can “speak through the symbolic language of nature” (Loili 112). Important to an application of Emerson’s approach to translation and its early effect on his own verse, such a seemingly translingual symbolic connection helps to build a strong case for his having anticipated Ezra Pound’s appropriation of the East in his influence of the American poetic tradition.

This is a book for scholars of American literature, in particular those who are deeply familiar with Emersonian scholarship, which I will admit up front that I am not. Nonetheless, despite the fact that my ignorance made it difficult to follow a good deal of what Sedarat had to say, as someone who, like Emerson and Pound, produced what some call “bridge translations” of classical Persian literature I resonated with what I was able to understand. (“Bridge translation” is a label signifying that I used an informant because I am not literate in Persian.) I wrote a little bit in Four By Four #41 about the translation work I’ve done and the ethical dilemma(s) attached to it. What I appreciated most about what I could follow of Sedarat’s argument is that he allowed me to place that work and my thinking about it in an American literary tradition I’d never really thought all that much about. In particular, I appreciated the way Sedarat set up a kind of continuum, with Emerson, who respected the integrity of the Persian poets he translated on one end—which is where I have tried to place myself—and, on the other, people like Coleman Barks and Daniel Ladinksy, who so deracinate the poets they “translate” (Rumi and Hafez respectively) that they are almost unrecognizable as the deeply religious, Muslim poets they were. (If you want to read a critique of Barks that is completely in line with but far more accessible than Sedarat’s, check out The Erasure of Islam from the Poetry of Rumi, by Rozina Ali.)

Four Things To See

I was originally going to post these videos during the “16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence,” from November 25 (International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women) – December 10 (Human Rights Day). Unfortunately, I was not able to do so, so I am including them in this month’s issue of Four By Four. I remember reading the text of Andrea Dworkin’s “I Want A Twenty-Four-Hour Rape Truce” in the late 1980s or early 1990s. I don’t usually post videos in this section of Four By Four, but I think juxtaposing them like this raises interesting and important questions.

I Want a 24-Hour Rape Truce (Text by Andrea Dworkin)

Survivor of Sexual Trauma Reveal an Important Truth (1in6)

§§§

These images are from the Cleveland Museum of Art and are in the public domain.

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, 1606–7, by Caravaggio

§§§

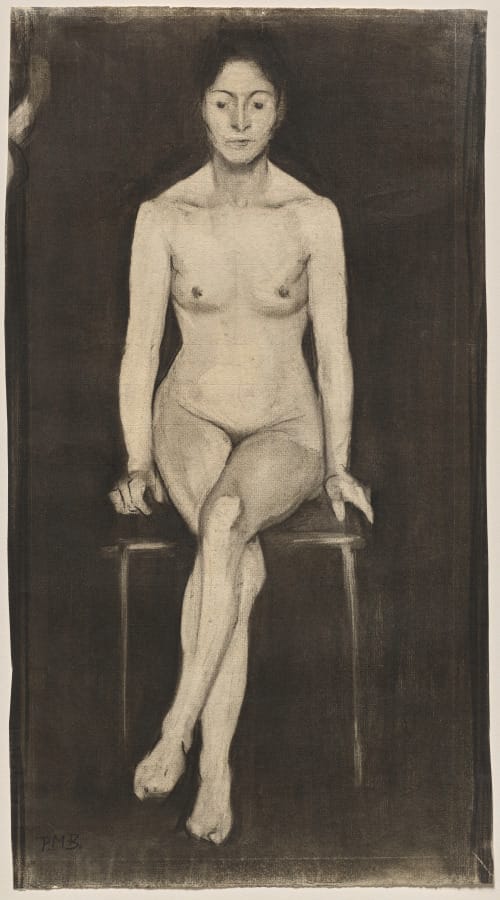

Seated Female Nude (Self-Portrait?), c. 1899. Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker died in 1907, just as the Expressionist groups in Dresden and Munich were forming. Nonetheless, the themes of her work prefigure the movement. This likely self-portrait reflects her desire to convey not the idealized appearance of the female body but rather its fundamental essence, stripped of all the world’s trappings. The sitter’s piercing stare invites the viewer to move beyond the body as flesh and blood toward her emotional or spiritual state.

Four Things To Listen To

Arash Sobhani - For Gina

§§§

Adam Silverman & Susan Gubernat - Elegy for The Earth (Performed by The Jenesais Choir)

Susan Gubernat was my officemate for many years. She is the author of The Zoo At Night and Flesh. In addition to this piece, she collaborated with composer Adam Silverman on the opera Korczak’s Orphans. Elegy for the Earth is a deeply moving song cycle.

§§§

Beth McCarthy - How Am I Supposed To Love Myself?

§§§

KATSEYE (캣츠아이) - Gabriela

Four Things About Me

I wrote these words on June 11, 1988. I don’t know what specifically I was responding to, but I definitely recognize the feelings of the younger me who wrote it:

To say “I love you” in a poem that means “I love you,” you need the obligatory irony that the language will never suffice for what you want it to mean. Otherwise, the poem will fail.

To say “I love you” to a friend who is not your lover, but whom you can imagine as a lover for a night or a week or a lifetime, you need somehow to keep their fear that you want your words to be a cage from ruining your friendship.

And if you want to say “I love you” to more than one person, you need to pick one as your lover and the rest to be “just friends” or you’ll be told you can’t make commitments. They’ll say you’re cheating someone out of the full and undivided attention the world wants love to be between two people.

§§§

I was speaking with a friend of mine who is not Jewish the other day about the different stances towards Israel that exist within the Jewish community in the United States and she asked me how I felt about the idea that Israel and its existence is a necessary component of Jewish identity and survival. Intellectually and historically, not to mention morally and ethically, I don’t think that position has ever truly held water, but I still get it emotionally. First, I am of the generation whose post-Holocaust Jewish education included the imperative that Jews needed some kind of safe haven should a situation like the Holocaust ever arise again. As a kind of prooftext for that, we were told, consider the experience of the role Israel was playing at that moment in the lives of the refuseniks, Soviet Jews who were persecuted for being Jewish and refused permission to emigrate to Israel. My own experience with antisemitism, which I wrote about briefly in this post on Israel and Palestine, also functioned for me as a real-life demonstration of what I was learning in Hebrew School.

I remembered something else during my conversation with this friend that I have not written about before. Part of what made the idea of Israel so compelling to me at the time was the possibility of being in a place where not only the overwhelming majority of people, but also the dominant culture was Jewish, where I would not have constantly to translate “being Jewish” for a Christian, or at least secularized Christian society that seemed entirely uninterested in really understanding what that identity was all about. Here’s one example from when I was in junior high school. There’s a major Jewish holiday call Sukkot (or Succos, if you’re Ashkenazi, like me) that occurs shortly after Yom Kippur. It’s a week-long holiday, on the first and last two days of which observant Jews do not work or go to school and follow restrictions on other activities similar to those they follow on Shabbat. My family was not orthodox, but I wanted to be observant and so my mother let me stay home from school on Sukkot so I could go to shul. When I was in seventh grade, on the second day of Sukkot, my junior high’s truant officer called my home to find out why I wasn’t in school that day. I don’t remember how I and not my mother ended up being the one to talk to them, but when I explained to her that I had stayed home because it was a Jewish holiday, she refused to believe me since she knew there were Jewish people working at the school who hadn’t stayed home. When I tried to explain the difference between observant and non-observant Jews, she didn’t believe me. Ultimately, though I have no memory of how, the situation was resolved and I was not charged with truancy. Nonetheless, it had made me aware of my own difference in a way that left a very bad taste in my mouth. I could point to more recent examples as well, but this one illustrates just how far back in my life this experience goes.

§§§

I’ve never been a jealous person. I don’t mean that I don’t experience jealousy. Of course I do. I mean that I have never been the kind of person who expects someone else to live their life in a way that protects me from jealousy, especially when it comes to love. On June 16, 1988, I wrote this in response to reading Jealousy, by Nancy Friday:

[W]e cannot expect other people to live according to our fears…jealousy is normal, is part of acknowledging the separateness of another human being—and…that acknowledgement is, in fact, a very, very important component—if not the entire basis—of love.

I think now I would rewrite that last sentence to read “That acknowledgement is, in fact, foundational to one’s ability to love another human being.”

§§§

I had a very serious girlfriend when I was in my twenties. We were together for almost seven years. At the beginning, however, for two or three of those years, we lived far enough apart and saw each other rarely enough that we decided it would be okay if we saw other people. If I remember correctly, we put it to ourselves like this: When we’re together, we’re together; when we’re not, what we do is our own business. We didn’t hide from each other the fact that we had friends of the opposite sex, but we never pressed each other to reveal more about those relationships than we wanted to. She spoke often, for example, about a guy she’d go dancing with on the weekends and I remember thinking that something in the way she talked about him indicated that they were probably also having sex; and I know I told her about the women who were my friends, one of whom became my lover for a while. Once, after my girlfriend and I were living close enough to each other that our “long-distance accommodation” was no longer necessary, she asked me outright if I’d been with another woman during our “don’t ask don’t tell” period. I saw no reason to lie, so I told her yes. She responded by punching me really hard in the arm. When I asked her why she’d hit me, she didn’t apologize. Instead, she explained that she was angry at herself, not me. “I thought I’d be able to tell if you were with someone else,” she said, “It bothers me that I couldn’t.”

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion