Dear Friends,

This third paid-tier preview picks up on a theme I’ve written about in a number of issues of Four By Four (#6, #19, and #28): the role music has played in my life. I’ve told parts of this story before, but I’ve never put it together in quite this way, framed by my friend Ronny’s belief in my talent and its potential. More to the point, I don’t think I would have found this perspective if I hadn’t decided to write about it as part of this month’s preview. Thank you for letting me share it with you. I wish you all a happy, healthy, meaningful and fulfilling holiday season.

—Richard

1. Exposition

Those are my hands over the keys at the grand piano that stood in the parlor of the dorm I lived in when I attended Edinburgh University in the summer of 1985. I’d dropped out of the graduate creative writing program I was attending earlier that year, and since I had no idea what I wanted to do next, my friend Ronny persuaded me to go with her to Edinburgh to study Scottish literature for a couple of months. I was a pretty good self-taught piano player by then, but I was less interested in performing for an audience than in the music I made when I sat alone and played only for myself. The presence of that piano, therefore—I did not have one at home—made me very happy, since I could play it in the moments of solitude I often sought out while my friends and classmates were out doing other things. Ronny took the picture of my hands late one afternoon when she happened to walk in on me while I was playing. She did not say anything to interrupt me, just crouched low enough to get the angle she wanted, snapped, and left.

2. Development

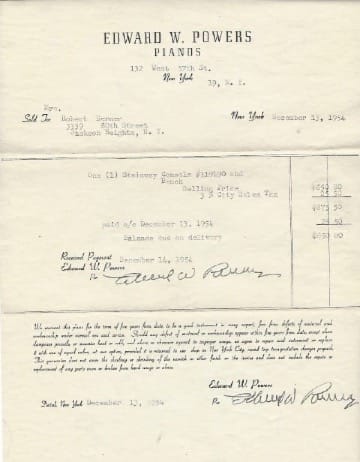

I say I was self-taught, but that’s not entirely true. I started playing piano when my grandmother showed me how to play the C major scale on the upright Steinway that stood in the dining room of hers and my grandfather’s apartment. She also gave me my first lesson in how to read music: whole notes, half notes, and quarter notes, in four-four time. Some years ago, my mother found the original sales receipt for that piano among my grandmother’s papers.

I didn’t know this back then, but my grandmother once had ambitions to sing opera and had, in fact, sung professionally on the radio when she was younger. (If I remember the story I’ve heard correctly, a young Jimmy Durante was one of her accompanists.) While she encouraged my interest in music, however, and in the piano, my grandmother actively discouraged me from taking music seriously, even once it became clear that I had a talent worth developing. I’d taken piano as a spring elective during my senior year in high school and had just played in the class recital Ernesto Lecuona’s Malagueña, a pretty remarkable feat considering that I had not previously taken formal lessons, that I did not have a piano at home to practice on, and that I had not played a watered-down transcription. I still have the copy of the sheet music I used at the time:

“You started playing too late,” my grandmother told me. “To be a concert pianist”—the only kind of professional playing that had any legitimacy for her—“you would have had to start taking lessons when you were still in grade school.” This stood in stark contrast to what my 11th grade English teacher had told me the previous year after hearing me improvise a little on the piano in the school’s auditorium. “I wouldn’t be surprised,” she said, “if in ten or fifteen years I’ll be able to come hear you play the blues in a bar in Greenwich Village.” I know now that I really was good enough that I could have made my teacher’s prediction come true if I’d wanted to—and I will tell you a little further on about the one time I did play in Greenwich Village—but at the time my grandmother’s words outweighed my teacher’s, which is why, though I briefly flirted with the idea, I didn’t major in music when I got to college. I have no regrets when I think about this now, but I do sometimes wonder if my grandmother was so insistent that I would never be good enough because she regretted, and resented, her own inability to pursue the career in music she had wanted.

§§§

The piano was not the first instrument I wanted to play. When I was in grade school, I asked my mother and stepfather if I could join the school orchestra. They were adamantly opposed, though I don’t remember them ever explaining precisely why. What I do recall quite vividly is George “demonstrating” for me the ways in which playing the instruments I was interested in would leave me “deformed” for life. If I chose the trumpet, he told me, my lips would become permanently puckered; and if I played the clarinet, he said, I’d end up with a face like a ferret’s, with my jaws frozen into the position required to hold the instrument’s mouthpiece. I was pretty sure he was making fun of me, though I was young and ignorant enough that I think part of me also worried he might be telling the truth. Either way, though, it was clear that he and my mother would not give me the permission I needed.

I was deeply disappointed, of course, but then, in 8th or 9th grade—my stepfather had left us and I don’t know why my mother didn’t stop me—I got a revenge of sorts by joining the local drum and bugle corps. I wanted first to be a drummer, but the man who ran the corps said he needed horn players, so I learned to play the bass baritone bugle instead. I practiced every day, which I am sure drove my mother and my neighbors a little bit crazy—hence, my revenge–and I eventually got good enough that my friend Marc and I talked seriously about trying to join either a drum corps that belonged to Drum Corps International, like the Bayonne Bridgemen, or auditioning for a professional corps, like the Hawthorne Caballeros. I don’t remember why that didn’t happen, but it didn’t.

§§§

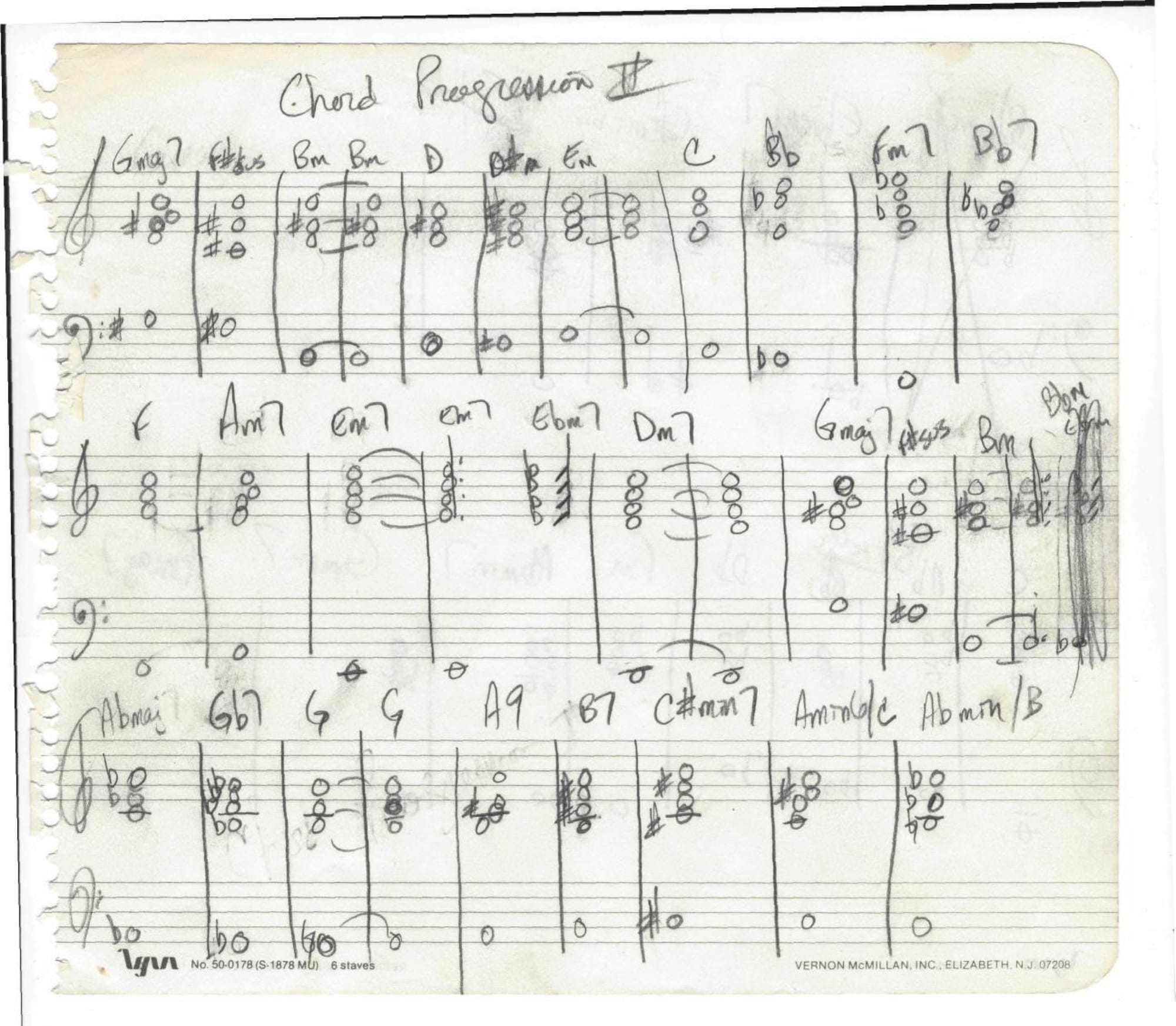

My grandmother’s discouraging words notwithstanding, I made time once I got to college to go to the piano practice rooms at least a few hours each week. I had no illusion that I would ever play for anyone but myself, but I was interested enough in music for its own sake that I took some theory and composition courses as electives. What I learned about reading chord charts in those classes turned out to be very useful when I became the accompanist for the musicals the kids in the drama program at Surprise Lake Camp put on two or three times each summer. I was the boys’ counselor, and I learned to fake my way through the music of shows that included Cats, A Chorus Line, Fiddler on the Roof, and Fame.

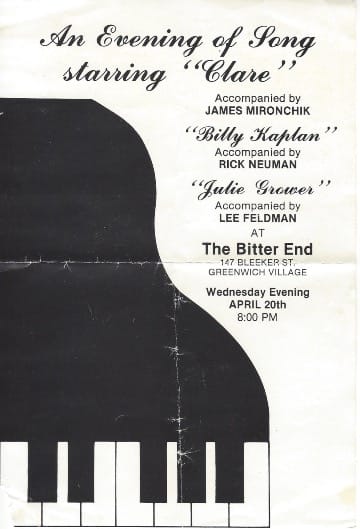

I stopped working at Surprise Lake the summer I went to Scotland with Ronny, after which I found a job with B’nai B’rith Hillel/JACY, a Jewish community organization that no longer exists. That’s where I met Bill, an aspiring singer-songwriter, with whom I became very close very quickly. I don’t remember which one of us suggested that we should collaborate on some of his songs, but once we started, making that music made very happy. Bill really wanted to play gigs, and he managed to get us one as part of a showcase at The Bitter End on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. I was excited, but the truth was that I thought of myself primarily as his cowriter and accompanist, a role I would have been just as happy for someone else to fill. I’d be lying, though, if I said I didn’t get a real thrill from seeing my name on the publicity flyer, even if it was completely misspelled:

My collaboration with Bill ended when our friendship did, and with it my desire to play on stage, which I’d been willing to do mostly because we were such good friends, not because I wanted it independently for myself. I still played piano for my own enjoyment, but with Bill out of my life, I made a conscious decision to focus my creative energy almost entirely on my writing.

3. Reprise

After that, I didn’t give much thought to playing music until I took the job I retired from in September as a professor in the English Department at Nassau Community College. A colleague who’d heard me play the host’s piano at a house party to which the entire department had been invited asked me how long I’d been playing. When I told her a version of the story I’ve written here, including the fact that I still didn’t own a piano, she very gently pointed out that with the salary I’d just started earning I could afford to buy one. I remember laughing out loud at the truth of what she’d said and at myself for not having realized sooner that my life was now my own in ways it had never been before, that I needed no one’s permission but mine to do something I’d wanted to do since I was a boy.

Because I lived in an apartment with very thin walls, I bought myself an electric piano with weighted keys. This way, as long as I wore headphones, I could play as long and as loudly as I wanted, at any time of the day or night, without disturbing my neighbors. I also bought myself a Yamaha SY77 MIDI workstation and what was then called a sequencer, a software program that allow me to compose on my computer. I was listening at the time to a lot of Tangerine Dream, especially albums like Melrose and Canyon Dreams, and I wanted to try my hand at making that kind of music. My songs, of course, were nowhere nearly as polished and professional as the ones on those CDs, but I enjoyed making them. Some, I thought, were actually pretty good. The five on this playlist are the only ones I still have. (Please note: if you’re reading this in an email, you may not see the audio player, in which case click here to listen.)

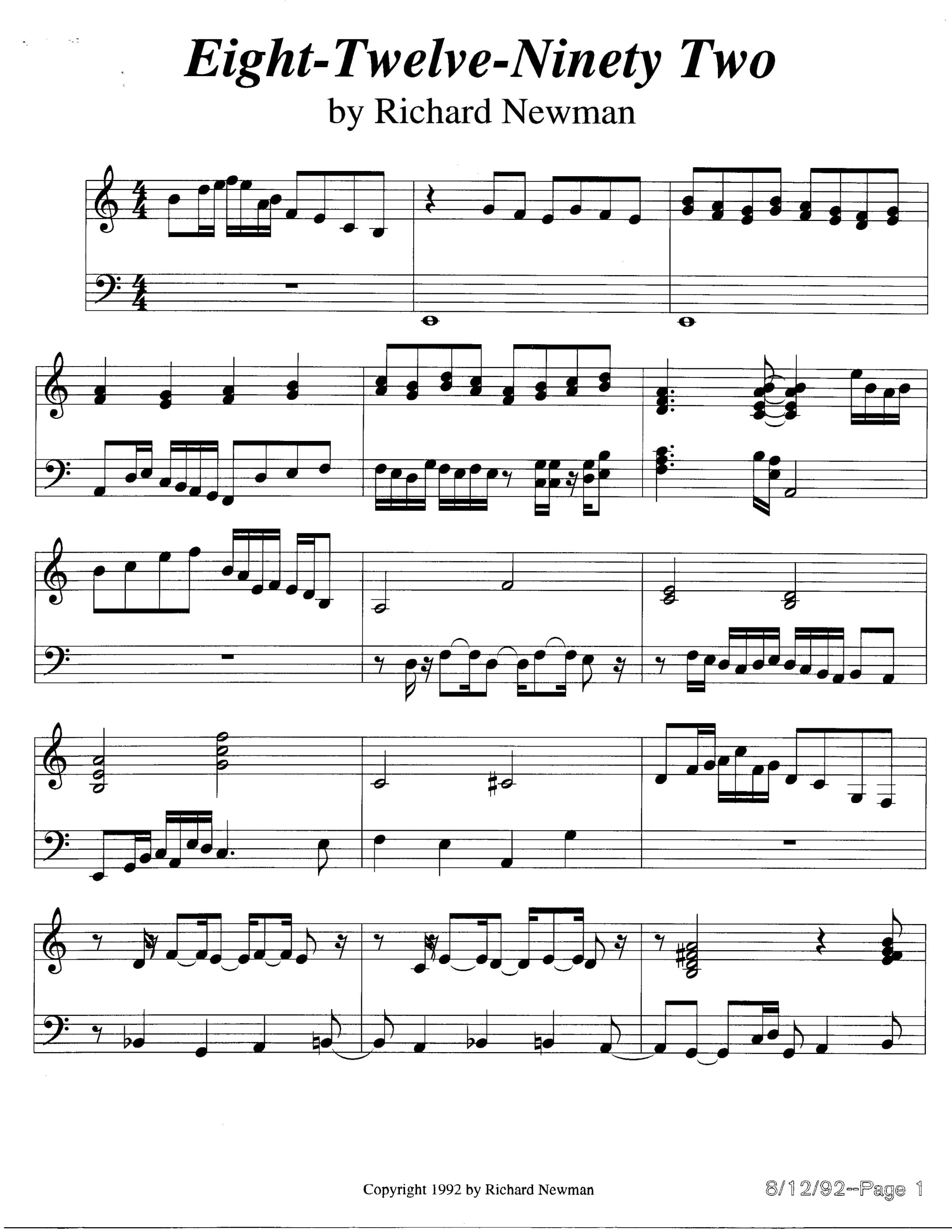

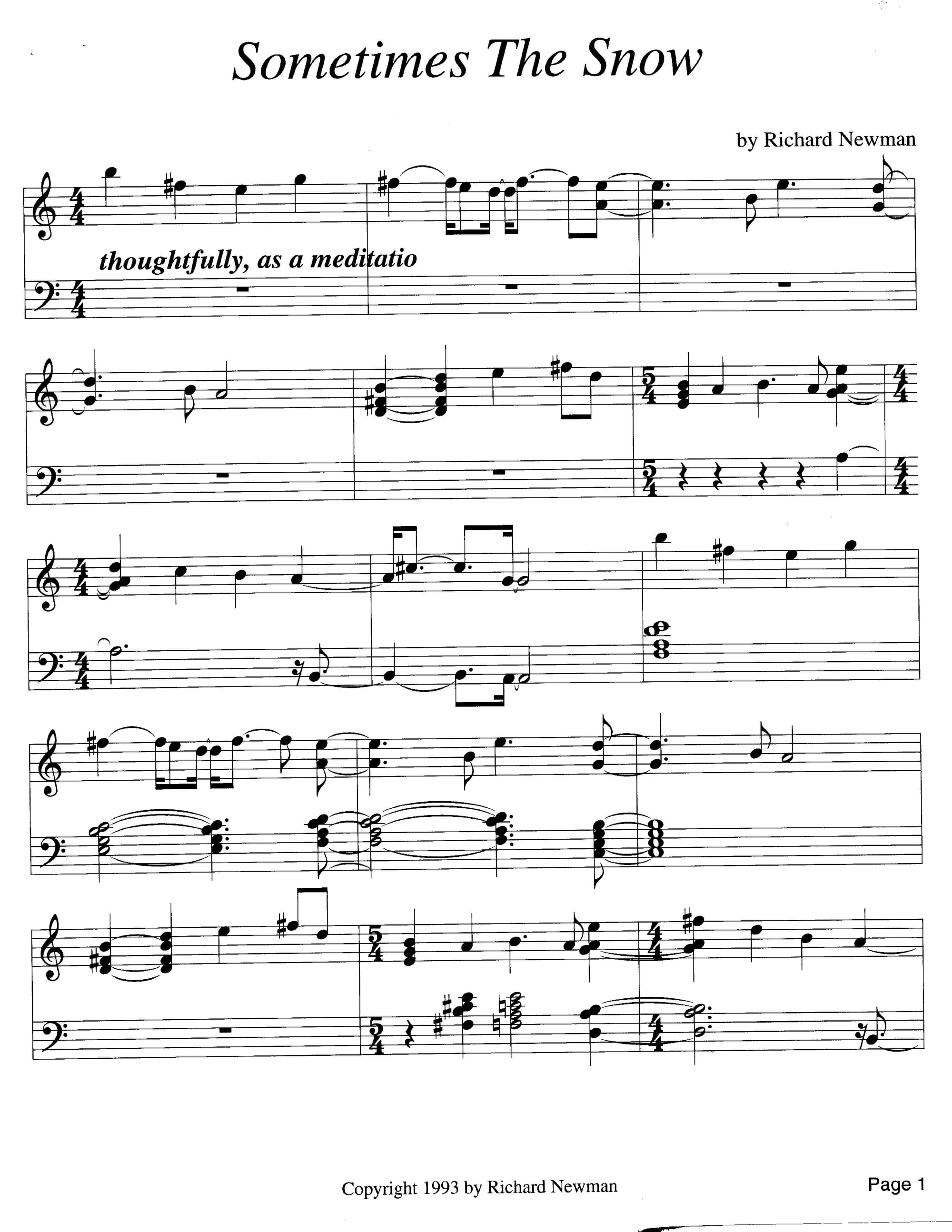

I made those songs by improvising the different tracks into the sequencer and then using the computer to shape those improvisations into finished pieces of music. The experience was very different from playing an acoustic piano and having what I played disappear into the air when I was done. It allowed me to think of myself for the first time as a composer. I even presumed to imagine I might one day write music that someone else would want to play, and so I also tried my hand at composing more intentionally, though I never did get the chance to hear anyone else play the songs I wrote.

After I got married, of course, and especially after our son was born, my life was no longer my own in the same way. I no longer had the luxury of spending as much time as I wanted on my own interests, which meant, ultimately, that I had to choose between writing and music. Since music had never really been more than a serious hobby, I chose writing. I didn’t stop playing piano—in fact we bought an acoustic upright when we moved into an apartment big enough to hold it—but I put the synthesizer away, stopped composing, and, inevitably, as life’s demands took more and more of my time, I played less and less, and the piano sometimes sat unplayed and silent for months and even years at a time.

I don’t regret this. Each choice we make about the future inescapably closes off any number of possible other paths we might have explored. I have, though, often missed the way music once filled a space in my life. Then, in 2023, when I published T’shuvah, my third book of poetry, I chose as an epigraph the words of Kol Ha’olam Kulo, a song that I have carried with me, and played on the piano, since I was in high school. The lyric is adapted from a saying by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov: “The world is a very narrow bridge, and the most important thing is not to be overwhelmed by fear.” Making that song a part of my writing life inspired me to create these two improvisations on the song’s melody, which I offered as free gifts to anyone who pre-ordered the book:

4. Coda

In April of 2021, my friend Ronny was murdered by her husband. She was my oldest friend and even though we had not been in touch regularly for quite some time—our very different lives and the physical distance between us being what they were—her death left a gaping hole in my life where just the knowledge that she was in the world should have been. Not too long ago, though, in a scene that could easily have come from a movie in which a character deep in grief over the death of a loved one feels like that loved one is somehow speaking to them from beyond the grave, I found something in my email archive that Ronny wrote to me back in 2018:

I remember your playing the piano in Edinburgh, both in the parlor and at a local pub during a session. Even though I had known you for years at that point, I was surprised by your talent…Who knows, if you had been encouraged to be a musician, would we have been denied your poetry? Would both have existed? I had the privilege to hear you improvise alone and play with other musicians at the pub that one night. Perhaps it is time to sit at a keyboard again. You might just have more to do there.

Maybe I do.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion